a) selected conversations:

![]()

1) Jennifer Inacio

![]()

3) Marcello Dantas

![]()

5) Luisa Duarte

![]()

7) Chris Bors

1) Jennifer Inacio

The55project: The Undercurrent

Conversationfor the occasion of the site-specific instalation The Undercurrent with The55project at the Miami Beach Botanical Garden (Miami).

3) Marcello Dantas

Creative Ecosystems, Boundaries of Art

Conversation on Art and Artificial Intelligence for the Arte 1 Tv Channel (SP).

5) Luisa Duarte

Colisão Conluio

Conversation for the occasion of the Colisão Conluio show at Nara Roesler gallery (SP).

7) Chris Bors

Altered Perceptions

Interview for the occasion of the Assembly show at Richard Gallery (NY).

b) selected words by others:

![]()

2) Gabriela Davies

![]()

4) Saul Ostrow

![]()

6) Frederico Coelho

![]()

8) Fernanda Lopes

About Space(s)

![]()

9) Daniel Gauss

2) Gabriela Davies

Intermédio

Text for the occasion of the Intermédio show at Athena Gallery (SP).

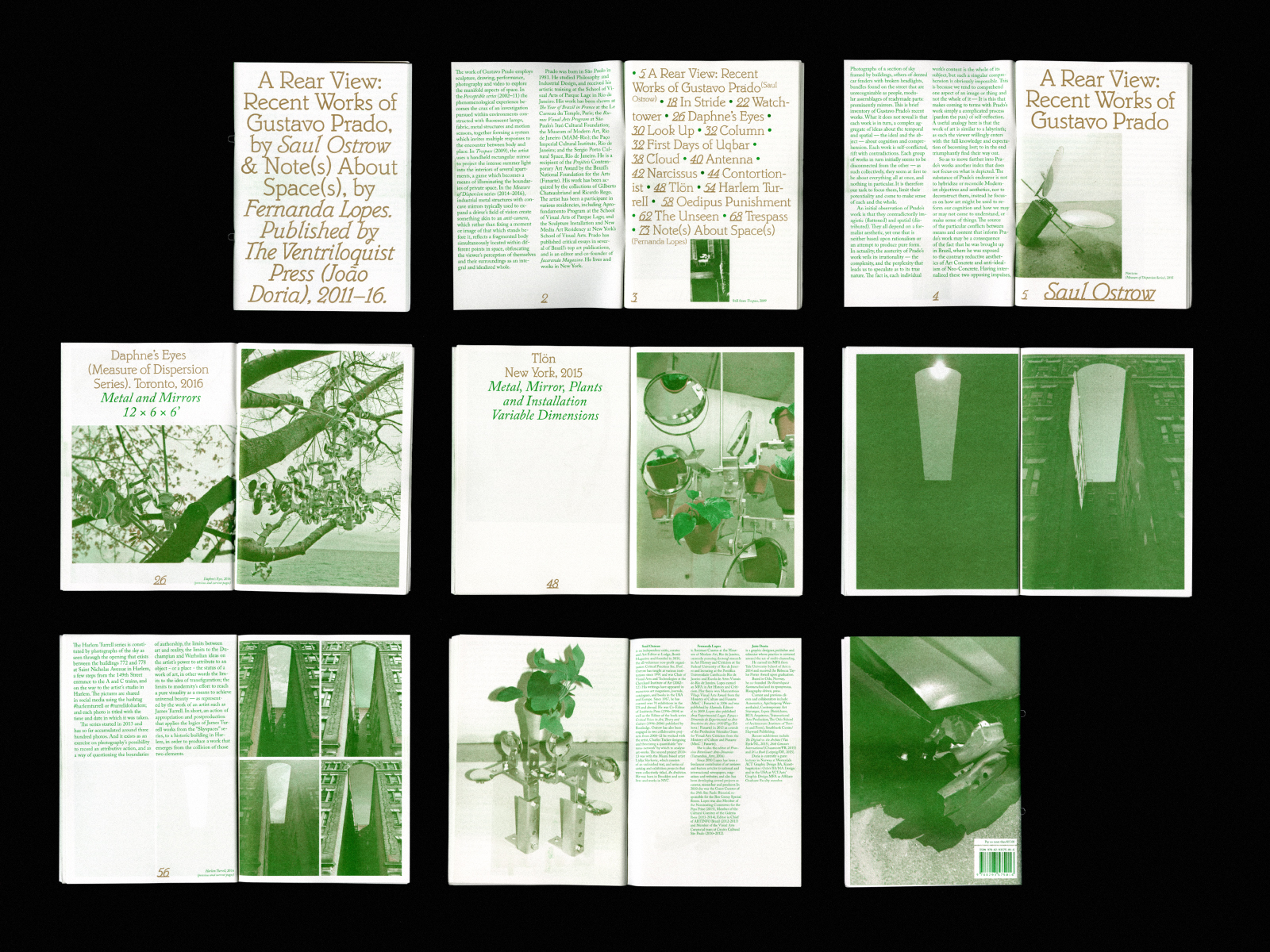

4) Saul Ostrow

A Rear View: Recent Work of Gustavo Prado

Text for the Artist’s Book (Note(s) About Space(s), Fernanda Lopes / A Rear View: Recent Work of Gustavo Prado, Saul Ostrow).

6) Frederico Coelho

Familiar Strangers

Text for the occasion of the Colisão Conluio show at Nara Roesler gallery (SP).

8) Fernanda Lopes

About Space(s)

Text for the Artist’s Book (Note(s) About Space(s), Fernanda Lopes / A Rear View: Recent Work of Gustavo Prado, Saul Ostrow).

9) Daniel Gauss

Heavenward Gaze

Essay for the occasion of the Assembly show at Richard Gallery (NY).

Words / Frederico Coelho

Familiar

A few years ago, Gustavo began an aesthetic experiment through his Instagram account. As a resident of New York for seven years, the daily commute to his studio in Harlem has become the grounds for a visual and conceptual examination. The series, entitled "Turrell of Harlem" (a work in hashtag), set the tone for a poetic synthesis of work presented at Lurixs. All of the works engage a series of concerns that unfold on various fronts, the first being a journey through a robust set of ideas produced by the history of art (i.e., the archive, tradition) and contemporary expectations. Here, nothing is gratuitous or excessive. In the works, Gustavo is observing the industrial materiality of our time through a network of meetings and disagreements, or, in the words used in the exhibition, of collusions and collisions.

Familiar

Strangers

Text for the exhibition “Collision Collusion Collision” at Lurixs gallery in August of 2018, Rio de Janeiro

A few years ago, Gustavo began an aesthetic experiment through his Instagram account. As a resident of New York for seven years, the daily commute to his studio in Harlem has become the grounds for a visual and conceptual examination. The series, entitled "Turrell of Harlem" (a work in hashtag), set the tone for a poetic synthesis of work presented at Lurixs. All of the works engage a series of concerns that unfold on various fronts, the first being a journey through a robust set of ideas produced by the history of art (i.e., the archive, tradition) and contemporary expectations. Here, nothing is gratuitous or excessive. In the works, Gustavo is observing the industrial materiality of our time through a network of meetings and disagreements, or, in the words used in the exhibition, of collusions and collisions.

If art history and the streets are these vectors of the invention of the new from possible collisions in the production of "familiar strangers," it is because Gustavo believes that it is not about producing new forms or claiming a personal style. Everything is loose on the air platform. It is about colliding things in intervals: small displacements whose gaps (between eye and reflex, concrete and glass, consumption and nature) allow the emergence of new meanings for the gaze—his and ours.

In "Harlem Turrell," for example, Gustavo references the North American artist James Turrell, who is celebrated for his experiments with light, color, and space, by documenting the brick landscape of a historical building. As shown in more than three hundred photos recorded over the course of the four years between 2013 to 2017, the repetition of the emptiness between the buildings displaces the material reference—space—in favor of the playful fluctuation of light—time. The gap between the buildings gains density when we retain Turrell's reference in our eyes. Exemplifying the artist's commitment to questioning institutional exhibition spaces, Gustavo's research allows us to acknowledge the art simulated by everyday landscapes. This process of approaching by edges, of rubbing surfaces, can also be seen in his metallic sculptures from the series “Measure of Dispersion.” In the title, Gustavo again privileges the contact between concepts whose overlaps activate a certain friction. The measure of dispersion—that is, the calculation of loss—can be extended to situations in which multiple mirrors—the measure—cause the dismantling of the gaze—the dispersal. Whatever perspective we approach, we automatically lose it. In the mirroring of the world, what we look at somehow looks beyond us. Its impeccably polished materials of each piece seem to refer to the place that minimalism holds in our aesthetic archive. But here the collision and the interval settle: each piece's materials are automotive, ordinary industrial products, displaced to a degree that its finished presentation eludes and overwhelms the senses.

And what happens when the history of art, rather than serving just as a reference, becomes the materials for this method of collusion and collision? While examining José Ribera's painting "Martyrdom of San Felipe" (1629), Gustavo found that something in this solemn religious scene does not fulfill his expectations: the saint's eyes wandering in a gaze of abandonment and loneliness. In Gustavo's rendition, he implements a modern grid—as baroque as the motif of painting—made of thousands of pieces of Legos and diminishes San Felipe's naturalistic condition as a man of the people. The overlap—another collision—between sacred iconography and the playful surface transforms martyrdom into an act without redemption and, for Gustavo, interrupts the possibility of a conviction. His desire to impose friction on these materials only reinforces this quest for semantic lapses that expand our interpretations.

If there is something "minimal" in the work of Gustavo Prado, it is his strategies. Minimalistic by nature, their effectiveness often reaches maximal strength. Whether in video, photography, sculpture or on canvas, we see in this exhibition Gustavo's mindset as a collector of material "traumas" and semantic breaches. His work, viewed together, draws attention to something central to our present moment: failure. His eyes look for veins that lead to symbolic familiarizes and approximations rather than resemblance. Without needing to smooth the edges, without claiming formal purity, Gustavo experiences the things he finds in the world guided by his ideas about art, design, city, and life. As in his beaten cars, every minimal difference serves to increase the illusion of sameness. An overarching trajectory present in his works is that, like reflections, they do not guarantee the integrity of the image and, instead, fracture the world into similarities and differences. In perceiving failure, Gustavo focuses our gaze onto what we can see, even when we do not see it.

Written by:

![]()

Frederico Coelho is a researcher, essayist and professor of Brazilian Literature and Performing Arts at PUC-Rio. He was assistant curator at MAM-RJ between 2009 and 2011. He participates as an associate researcher at the Center for Studies in Literature and Music (NELIM) at PUC-Rio. He wrote articles for magazines and periodicals such as Sibila, Historical Studies, Margins, Erratic, Lump, National Library History Magazine, Collection, Contemporary Brazilian Culture, Ramona and Vogue. In addition, he published articles in collections on music, football and behavior and organized, alongside Santuza Naves and Tatiana Bacal, the book MPB - Entrevistas (Editora UFMG, 2005). He worked as a researcher and published an article in the catalog of the exhibition Tropicalia - A Revolution in Brazilian Culture (Cosac Naify, 2006). In 2006, he participated in the research and content elaboration of the website He organized three books in the Encontros series, by Azougue Editorial: Tropicália with Sérgio Cohn (2008), Tom Jobim with Daniel Caetano (2011) and Silviano Santiago (2011). He launched the books Museum of Modern Art - Architecture and Construction (organizer, Cobogó, 2010), Book or book me - the Babylonian writings of Hélio Oiticica (EdUERJ, 2010), I, Brazilian, confess my guilt and my sin - marginal culture in Brazil 1960/1970 (Civilização Brasileira, 2010) and Contemporary Brazilian Painting (organizer with Isabel Diegues, Cobogó, 2011.

Frederico Coelho is a researcher, essayist and professor of Brazilian Literature and Performing Arts at PUC-Rio. He was assistant curator at MAM-RJ between 2009 and 2011. He participates as an associate researcher at the Center for Studies in Literature and Music (NELIM) at PUC-Rio. He wrote articles for magazines and periodicals such as Sibila, Historical Studies, Margins, Erratic, Lump, National Library History Magazine, Collection, Contemporary Brazilian Culture, Ramona and Vogue. In addition, he published articles in collections on music, football and behavior and organized, alongside Santuza Naves and Tatiana Bacal, the book MPB - Entrevistas (Editora UFMG, 2005). He worked as a researcher and published an article in the catalog of the exhibition Tropicalia - A Revolution in Brazilian Culture (Cosac Naify, 2006). In 2006, he participated in the research and content elaboration of the website He organized three books in the Encontros series, by Azougue Editorial: Tropicália with Sérgio Cohn (2008), Tom Jobim with Daniel Caetano (2011) and Silviano Santiago (2011). He launched the books Museum of Modern Art - Architecture and Construction (organizer, Cobogó, 2010), Book or book me - the Babylonian writings of Hélio Oiticica (EdUERJ, 2010), I, Brazilian, confess my guilt and my sin - marginal culture in Brazil 1960/1970 (Civilização Brasileira, 2010) and Contemporary Brazilian Painting (organizer with Isabel Diegues, Cobogó, 2011.

words / Saul Ostrow

Photographs of a section of sky framed by buildings, others of dented car fenders with broken headlights, bundles found on the street that are unrecognizable as people, modular assemblages of readymade parts: prominently mirrors. This is brief inventory of Gustavo Prado’s recent works. What it does not reveal is that each work is in turn, a complex aggregate of ideas about the temporal and spatial – the ideal and the abject — about cognition and comprehension. Each work is self-conflicted, rift with contradictions. Each group of works in turn initially seems to be disconnected from the other — as such collectively, they seem at first to be about everything all at once, and nothing in particular. It is therefore our task to focus them, limit their potentiality and come to make sense of each and the whole.

Prado’s restless movement from meaning to sense, from intention to indirectness reflects the influence of a contemporary, post-Modernism that responds not only to the collapse of Modernism’s utopian ideals and rationalism, but also to the dystopian vision of 1980s Post-Modernism, which was premised on simulation, replication, and spectacle. By occupying neither one or the other position, Prado pits one against the other producing uncertainty and attentiveness. He in a non-hierarchical — non-historical manner subverts the limitations of the art object as a conveyance of meaning. For instance, what he presents are assemblages of either common events, or in the case of the mirror pieces — cheap mass produced materials that are pragmatically combined to diverge from their intended purpose, as the surveillance and blind-spot mirrors, which are to be found in the subway, shops, and on the streets. As is the nature of assemblages their components simultaneously retain their identity while lending some of its qualities to the greater whole. So while his works may initially appear to be idealized and abstract, they are in all-ways mundane: in this context Prado uses the art object as a means both of self-reflection and conveyance.

A Rear View: Recent Work of Gustavo Prado

(2016)

Photographs of a section of sky framed by buildings, others of dented car fenders with broken headlights, bundles found on the street that are unrecognizable as people, modular assemblages of readymade parts: prominently mirrors. This is brief inventory of Gustavo Prado’s recent works. What it does not reveal is that each work is in turn, a complex aggregate of ideas about the temporal and spatial – the ideal and the abject — about cognition and comprehension. Each work is self-conflicted, rift with contradictions. Each group of works in turn initially seems to be disconnected from the other — as such collectively, they seem at first to be about everything all at once, and nothing in particular. It is therefore our task to focus them, limit their potentiality and come to make sense of each and the whole.

An initial observation of Prado’s work is that they contradictorily imagistic (flattened) and spatial (distributed). They all depend on a formalist aesthetic, yet one that is neither based upon rationalism or an attempt to produce pure form. In actuality, the austerity of Prado’s work veils its irrationality— the complexity, and the perplexity that leads us to speculate as to its true nature. The fact is, each individual work’s content is the whole of its subject, but such a singular comprehension is obviously impossible. This is because we tend to comprehend one aspect of an image or thing and not the whole of it — It is this that makes coming to terms with Prado’s work simply a complicated process (pardon the pun) of self-reflection. A useful analogy here is that the work of art is similar to a labyrinth; as such the viewer willingly enters with the full knowledge and expectation of becoming lost; to in the end triumphantly find their way out.

So as to move further into Prado’s works another index that does not focus on what is depicted. The substance of Prado’s endeavor is not to hybridize or reconcile Modernist objectives and aesthetics, nor to deconstruct them, instead he focuses on how art might be used to re-form our cognition and how we may or may not come to understand, or make sense of things. The source of the particular conflicts between means and content that inform Prado’s work may be a consequence of the fact that he was brought up in Brazil, where he was exposed to the contrary reductive aesthetics of Art Concrete and anti-idealism of Neo-Concrete. Having internalized these two opposing impulses, Prado’s works are alternately purist and mundane, transcendent and commonplace. For instance, the photos that make up Harlem Turrell are minimalist and beautiful, yet they consist of little more than a coffin shaped section of the sky framed by apartment buildings – The contained area is sometimes flat grey, blue or with fluffy white clouds, etc.

But there is more to Harlem Turrell than some gesture mean t to aestheticize a section of sky., 300+ photographs presently make-up this work. This may leads us to ask; who orders their life so they can on a regular basis take photographs of some chance place, which reminds them of a James Turrell installation. It is not the sky, or the unobserved moments that Prado documents or calls our attention to, it is the multiple contexts within which this work exists — from photography’s documentary tradition to the sensuous aesthetic of transcendentalism. Viewers join the artist in believing that these photographs are meaningful, if seen through whatever index of their choosing. Subsequently they form an archive whose content is understood phenomenologically, cognitively, aesthetically, culturally and even politically. Within these various frameworks the repetitions and variations that these photographs record rather than being redundant come to make still some other sense.

A still longer index would identify Prado’s work not only in accord with their imagery, media, inferences, and shared logics, but also his employment of duration, repetition, and variation as terms and conditions relative to the production of symbolic representations, as well as their presentation. Such a list includes: variability, eventfulness, object-less-ness, site/site-less-ness, deferral, discontinuity, cognition and comprehension, interiority and exteriority — things in kind — types — degree, etc. This list requires another of the potential forms by which these may be actualized would include: assemblages of assemblages, modularity, seriality, and the Readymade. Prado applies this still incomplete index to the range of media, strategies and subjects that he works with; this is the reason why, at first, his works appear to be disconnected from one another. Yet, when their structures and themes are compared rather than taken in isolation, it becomes apparent that Prado by moving back and forth between the literal and objective, the conceptual and practical asserts the indeterminacy of experience and meaning. By exposing the discontinuity, complexity and multiplicity of our realities, Prado works define the ‘space’ of art as one that is simultaneously mythic, symbolic, and real. It is from this that this essay takes its title, which too is intended to call up the multiplicity of contradictorily references that range from that of the warning on a rearview mirror: that objects may appear closer than they actually are, to the idea that the work of art that we view is always already moving away from us.

Prado’s restless movement from meaning to sense, from intention to indirectness reflects the influence of a contemporary, post-Modernism that responds not only to the collapse of Modernism’s utopian ideals and rationalism, but also to the dystopian vision of 1980s Post-Modernism, which was premised on simulation, replication, and spectacle. By occupying neither one or the other position, Prado pits one against the other producing uncertainty and attentiveness. He in a non-hierarchical — non-historical manner subverts the limitations of the art object as a conveyance of meaning. For instance, what he presents are assemblages of either common events, or in the case of the mirror pieces — cheap mass produced materials that are pragmatically combined to diverge from their intended purpose, as the surveillance and blind-spot mirrors, which are to be found in the subway, shops, and on the streets. As is the nature of assemblages their components simultaneously retain their identity while lending some of its qualities to the greater whole. So while his works may initially appear to be idealized and abstract, they are in all-ways mundane: in this context Prado uses the art object as a means both of self-reflection and conveyance.

Using images and situations that are familiar but do not readily conform to the known symbolism, Prado generates conditions that he believes will cause the spectators to feel acutely self-conscious of varied aspects of their existence. Constructed from the incidental — this non-hegemonic realm generates a state of otherness, which are neither here nor there, that is simultaneously physical and mental, such as the moment when we see ourselves in a mirror, or imagine the narrative behind some inexplicable incident such as that the image of a dented fender. One may conclude from this that Prado analogously finds art to be a space within which differences are affirmed and denied as both real and imagined — as both fixed and dynamic. Inversely, his work asserts that art is a real space within the world we live in, but it lies outside or beside most places. In this art may be thought of as forming a heterotopia — a place that operates by its own logic and reasoning. Consequently, though it is possible to indicate art’s location in reality as being that of the institution and the marketplace - even these spaces are defined by their own ecologies and logics. From this we might deduce that Prado’s ambition is to via art, extract from and insert into our world things and events that have few or no intelligible connections with one another so as to require us to comprehend them in a non-habitual manner. This space subsequently is one of constant vigilance for it requires attentiveness and engagement, and simultaneously the inverse: deferral and indifference.

Let us imagine we find ourselves among art works by various artists who have been asked to install works in the corridors of a new luxury apartment building that a real estate developer is seeking to promote. Prado installs his photographs of those invisible people who occupy what can only be seen as marginable spaces. Prado’s images with their pain, formalism, and historicity, in a gallery or museum space would be little more than yet another social document of indifference and desperation, but in these hallways each image becomes a specter, haunting that specific space – each encounter be a silent accusation. Let us then imagine these same images presented without commentary in a newspaper format that is distributed free and whose only text is an appeal for donations to help the homeless. Here his photographs become an appeal. These alternate, aesthetic and social practices implicitly come to exist side-by-side reflecting opposing paradigms, which mirror aspects of the real world whose reflections fracture into multiple realities, including those of differing and conflicting ideologies, objectives, practices and responses.

A still broader inventory would have to include Prado’s images and structures’ relations to the their implicit and explicit social and the political content or Everyday-life. This inventory would expose the fact that though he exploits structuralism’s ability to identify analogies between apparently different forms, he is not a structuralist – in that for him the shared norms that frame his works are impositions – that serve only as hindrances, which Prado seeks to clear away because they induce habits on the part of the viewer that both aestheticize and devalue the very things he would have us consider. The events he focuses on and articulates are used to evade the dominant structures, which would make his work, literary, aesthetic and therefore intelligible – turn them into being about this or that. Instead, within the structures and habits that constitute the norm, Prado finds the relations of power that bear upon and determine those a priori meanings and expectations that obscure the complexity of everyday events. In response to this, Prado deals with precarious relationships between form and content by creating ambiguous, though immediately recognizable situations, inducing a sense of uncertainty that provokes the viewer to reconcile the visual information with a multitude of unstable references, e.g. we see a homeless person who is no longer recognizable as human being and we immediately understand this as a social critique premised on humanist or moral notions yet, Prado’s aesthetic instead is meant to have us consider the question of how and why we come to that reading, and whether ethically do we have a similar response when we come upon these people in our world.

From a Deleuzean perspective — what Prado tries to articulate is: how every action and every event is an exchange that denotes the ebb and flow of power, with relevance to differing aspects of daily life, and subsequently what is the economy of de-humanization and objectification. The position his work takes relative to this economy is that of the horizontal axis — a position engagement — we see only that which is before us, rather than that of the vertical, which provides distance — and an overview. The horizontality of Prado works’ cuts across modes of representation, media-forms and subjects, likewise they cut through language, meaning, metaphor — instead, Prado seeks analogy and comprehensions built on the notion that these are all the contrasting phases of one and the same things eg. smooth and rough are both terms applicable to surfaces and motion.

The dismantling of dichotomies permits Prado to envision his work as marking out a trajectory that escapes the narrowness of a world built on polarities. Obviously, there are limits to the degree to which this reworking of rationality may be done and the affect that it may achieve; for instance, it cannot re-form modernity or our sense of being in totality– but it may cause us to reflect upon the complexity and unrealized potentiality of our own everyday endeavors, which we have been taught to think of as comprehensible contiguous events rather than a construct of fragments, gaps, and discontinuities. It is only our habits of thought that permit us creating aggregates , which result in objects that are then in turn negotiated, improvised, and navigated and made symbolically consistent resulting in a somewhat predictable real.

Based on his desire to intervene in the simulacra of the everyday and the world of objects, Prado’s work may be considered political, not in the usual sense of exposing some aspect of the economy of power or its abuse. Instead, he compels his audience to come to terms with an image-world that is constantly being ordered, framed, disassembled, and re-assembled for and by them. In this sense, Prado makes the conflict between the symbolic (the blindness of Oedipus) and the substantial (the damage caused by a crash) visible; this is the conflict between the object as document and as an objectification. Prado’s employs this differing states so as, to point to everything, including his own work. In this, he questioningly appropriates a wide range of unresolvable issues, such as: the boundaries of authorship, the aesthetic nature of reality, the semiotics of objects / places, the status of event or, the limits to the idea of transfiguration of the real, etc..

Still looking at Prado’s photo series Oedipus Punishment, a parallel can be drawn between the damaged headlights that can no longer light our way, and the blinding of Oedipus, who puts out his own eyes, providing us with still another inventory. The key here is that Prado biography, he had been brought up to understand that “the light” and truth are comparable. For Catholics “Truth” illuminates one’s way in the world — the truth is a thing that shines, gives light – revealing not only itself but also all that surrounds it. Symbolically, such awareness provides a greater chance of avoiding deception. In this context, we can connect how Prado has used light as both a subject and a medium – be it in his colored-light-filled-rooms and interactive environments, or in his current use of mirrors, photography, and video.

A less obvious inventory relative to the metaphorical and symbolic function of light and belief can be formulated here — its principle concerns are the conditions and terms of existence that originate with The Enlightenment. Since the 60s these master narratives have been the object of an extensive self-reflective critique. This index references the core of Western society’s operating system and that of Capitalism. It includes the secularization of such Christian notions as illumination, truth, essence, bare life, awareness, etc. These terms define human existence within the course of self-realization – cognitive development — awareness — which defines the process of transcendence and transformation. This process is a consequence of the needs, abstractions, and comprehension that come into being given our collective and individuated — public and private interaction with the external world, which is inclusive of people and things.

Underlying all of these indexes is the economy of bare life (bodies) and qualified life (one who may act). These terms designate the subject and object of social inclusion and exclusion (as defined by The Law). The key clue that these concepts are in play in Prado’s works is most apparent and obvious in the photo series the Unseen – which depicts those who have arrived at a state of bare life and are therefore almost unrecognizable as human beings. Though persistently striving to live – they appear to have become objects that are further objectified by being photographed. Those images make them present in absentia, while giving them recognition, yet they still exist without identity. So while the Unseen best illuminates and gives presence to this idea of the excluded (excepted), it also puts in an appearance in Prado’s mirror pieces for this address the idea again of privacy – the notion that one has a right to certain expectations. It is this existentially based system that Prado’s work disassembles, and de-structures, while using it contradictorily as an armature to generate dispersed of discontinuous objects/ categories/ situations.

The video Tresspass can be read within the context of the qualified life, as the inverse of the Unseen, it depicts people coming to their windows to shew away the artist, wanting him to stop recording their windows – in this moment, their windows become an interface between their public and private lives and the artist has become an intruder and a threat. Here, the qualified life becomes defined by an expectation of privacy — that is the idea they have the right to choose not to be seen because they participate in a social economy that permits them privacy. The mirror sculptures combine and confuse this notion of public exposure and privacy, for it permits an indirect observation. By looking into the array of rear-view and security mirrors, the viewer becomes invisible — that is, unseen, while the viewed is reduced to image/object. Within the resulting panopticon, viewers are led to believe they have a comprehensive view of their surroundings — yet in actuality the mirrors serve as lens that frame and exclude all that is outside the frame — in this the mirror pieces are not unlike the photographic works.

So now, we might add to Prado’s inventory the notion of distraction and extraction, as a corollary to interiority and exteriority, and to horizontality and verticality — these are not spatial terms here, instead they are relational ones. By emphasizing exchangeability, and multiplicity, Prado provides a framework for generating textual complexity. This economy is not stable and fixed; rather it is one in which successive complimentary and contradictory narratives displace and replace one another. This is not because the narratives are arbitrary — it is because no one narrative can tell the whole of the story that is given representation by Prado’s works. This is because each individual component tells its own tale and then also contributes to and modifies that of another. Each component exists as part of, and independent of the specifics of the work that they are deployed within; the task that the viewer is offered, is to engage coding, decoding, or recoding each component rather than to synthesize a whole, though they may insist on doing so.

Though not the final inventory, I will conclude with one that consists of 3 stages of a single process; these are the pre-cognitive (perception), the cognitive, and the act of recognition. The first is the realm in which the mind becomes aware of a stimulus — a process that is reflexive and chaotic. The second is the realm of concept development – the organization of the sensations that are the result of perception. The final is recognition; concept application — acts of recall in which the concepts that have been formulated are applied to each new situation, or encounter. This last stage consists of filters, shortcuts, and modes of behavior and thought that in effect order and limit our experiences — Recognition is the process within which things (all that is encountered or thought) comes to be comprehended based on whatever set of concepts that come to be (individually and collectively) applied to them. In a sense our comprehension of the world is a rearview — one that via memory looks back to past associations. This is why I have emphasized that the art-work as all other things comes to be understood only in parts, yetthe limitations our understanding places upon it does not affect its potentiality, or its complexity. In this context we may assert that Prado in recognition of this, has constructed his works so that the components that permit us to comprehend his works both physically and conceptually may be simultaneously, or sequentially connected, reconfigured, disconnected or inhibited.

Within the process of recognition nothing by virtue of its being is itself: nothing stands outside this system of differentiation and deferral. To apply this Derridean notion of différance to the work of art, the subject and content of the work can only reference a multiplicity of things (ideas, experiences, propositions), which in turn are mediated by the means of their conveyance and those of their reception, subsequently, some part (perhaps, most) of the thing is deferred. The viewer’s objectification fills in the resulting gaps and form an illusionary continuity and unity. In Lacanian terms, this is the realm of the symbolic — the space of power, order and discourse — the means by which the Real (that which occurs without reason of intent) is held in check. With this in mind, we can understand works that Prado produces as an exploration of representation (recognition) and as distinct from lived experience (cognition). Given this economy one may imagine that Prado finds value in the partiality of what may be transmitted, and the surplus it generates — From these paltry means Prado builds a model of how one may resist instrumentality, and remain a humanist without succumbing to idealism, or any apparent ideology.

Text for the Publication bellow:

Written by:

Saul Ostrow

is an independent critic, curator and Art Editor at Lodge, Bomb Magazine and founded in 2010, the all-volunteer non-profit organization Critical Practices Inc. Prof. Ostrow has taught at various institutions since 1991 and was Chair of Visual Arts and Technologies at the Cleveland Institute of Art (2002–12). His writings have appeared in numerous art magazines, journals, catalogues, and books in the USA and Europe. Since 1987, he has curated over 70 exhibitions in the US and abroad. He was Co-Editor of Lusitania Press (1996–2004) as well as the Editor of the book series Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture (1996–2006) published by Routledge. Ostrow has also been engaged in two collaborative projects. from 2008–12 he worked with the artist, Charles Tucker designing and theorizing a quantifiable “systems-network” by which to analyze art-works. The second project 2010–13 was with the Miami based artist Lidija Slavkovic, which consists of an unfinished text, and series of catalog and exhibition projects that were collectively titled, An Ambition. He was born in Brooklyn and now lives and works in NYC.

words / Daniel Gauss

(For Meer - 2019)

Laocoon is the earliest known example of a work showing the heavenward gaze of a person who is suffering and seeking deliverance from a god or gods. The work is highly ironic as Laocoon is a just man being unjustly harmed by the very gods from whom he unwittingly seeks rescue. That type of heavenward gaze, nonetheless, became a staple for western artists depicting Christian martyrs who submitted to unjust pain and persecution while calling on a just God to provide salvation in a new life. We see Brazilian artist Gustavo Prado revisiting this gaze in his work at Galerie Richard on Manhattan’s Lower East Side while also questioning the extent to which artistic means and messages have often intersected at a level of dominant culture and economic expectations.

Heavenward Gaze

(For Meer - 2019)

Laocoon is the earliest known example of a work showing the heavenward gaze of a person who is suffering and seeking deliverance from a god or gods. The work is highly ironic as Laocoon is a just man being unjustly harmed by the very gods from whom he unwittingly seeks rescue. That type of heavenward gaze, nonetheless, became a staple for western artists depicting Christian martyrs who submitted to unjust pain and persecution while calling on a just God to provide salvation in a new life. We see Brazilian artist Gustavo Prado revisiting this gaze in his work at Galerie Richard on Manhattan’s Lower East Side while also questioning the extent to which artistic means and messages have often intersected at a level of dominant culture and economic expectations.

The Buddha observed a major insight into psychological or emotional pain. If you feel pain and then desire the pain to go away, the pain will increase (if you desire to sustain pleasure, you will vitiate that pleasure). Tolerable pain, which will go away naturally, can be aggravated into serious and chronic pain through the human will. Furthermore, we often feel the emotional pain we are experiencing should not even be happening and we employ psychological methods which make the pain worse and longer lasting. We, paradoxically, get a painful response to pain while seeking palliation; we allow pain to perpetuate and aggravate pain. We treat pain as if it never should have happened, but it would be much better to just let it happen and let it disappear.

The heavenly gaze of Christian martyrs means that the martyr has submitted to pain, is not trying anything to save himself from it, and is waiting for and open to divine balm, in the form of a new life. Indeed, the heavenly gaze of martyrs may be in regard to a final, ultimate pain, similar to the excruciating pain of Jesus, for which there is no remedy to be found in the human will, but which expiates through divine intercession. When Paul wrote that Jesus expiated our sins, he was not referring to a magical ritual, but to a process of transformation and overcoming through the acceptance of pain which cannot be overcome through our own choosing.

So Prado presents his martyrs using Legos. First, this can be interpreted as a type of protest against artists who require massive amounts of money and material to produce work, as well as extensive logistical efforts to transport their work, as a way to confer gravitas to it (think of Richard Serra, for instance). Prado wishes to create art which can be assembled from materials in virtually any location he might travel to. Legos are a universal toy and, as such, become perfect as a means to replicate art in any locale. Every material also, however, carries a message with it. To use Legos to represent suffering could be an attempt to intimate the intense joy underlying and masked by suffering, the joy available once one goes through or conquers suffering or a childlike approach to suffering which might allow one mastery of it. A cynic could even suggest the Legos might represent a childish belief that God does not want us to suffer and will gladly intercede. Prado, therefore, falls into the pop art tradition that challenges whether a significant message has to be delivered with academically accepted, expensive or even pretentious materials.

By radically changing the material through which the martyrs are presented, Prado could also be inviting a radical reassessment of how these martyrs and suffering have been used in the history of art. In heavily Catholic Brazil, these martyrs are literally iconic and are to be admired, worshiped and prayed to. The images almost serve a magical function. By stripping the martyrs of any pretense, Prado invites a closer look at suffering beyond allegory and magic. These materials are accessible – these martyrs are no longer so divorced from us, we are no longer so divorced from their experience. The message of suffering and how it must be borne now becomes available through art to all of us in an inexpensive and readily accessible form. We, conceivably, could make these pieces ourselves.

Included in the show are also various sculptures created with mirrors. Again, Prado chooses to use materials accessible to everyone, which can be bought anywhere, so that his art can be assembled anywhere. He divorces himself, to as great an extent as possible, from the economic factors often needed to create and transport large-scale works, keenly aware that art and economics have been in bed together in the art world for too long and to too little beneficial consequence. Jean-Luc Richard explained to me that Prado also enjoys allowing folks to see themselves distorted and reversed, perhaps undermining one’s expectations that the mirror should provide predictable visual feedback and providing a more provocative view of oneself.

These mirrors also allow folks to view the natural world differently as Prado has sometimes placed his sculptures in trees to represent the possibility of expansion and growth while he once placed mirrors under palm trees to allow a type of reversed perspective. He has used mirrors to reveal unique aspects of an outdoor Calder sculpture and at a music festival to redirect attention to the crowd as the real subject of the event. Yet, the pieces can also stand in for the proliferation of surveillance systems in our lives. Indeed, Jean-Luc Richard explained to me that Prado likes to place his mirror sculptures in collectors’ apartments in unexpected, out of the way places.

The mirror sculptures, to me, represent an over-reliance on a process involving a scrutiny of the observable to get at the unobservable, or the limits of this process. We create our metaphors and symbols through the process of capturing and processing light, but, ultimately, we have to go beyond metaphors and symbols and engage in a more hidden inner reality of our motives, emotions, desires and cognitive processes to rise as human beings. I think the martyrs and mirrors are actually connected in this show. The martyrs turn their gazes away from themselves, heavenward, away from the mirror. Yet, Prado seems optimistic about the mirror, believing that with its proper use it can yield new perspectives and even invite greater self-examination.

Images of the show Assembly at the Richard Gallery, 2019:

![1.]()

1. In Depth (2019), Measure of Dispersion Series

![]()

2. Diego and Mary (2019), Ascension series

![]()

3. Spectre (2019), Measure of Dispersion series

![]()

4. Computer Love (2019), Measure of Dispersion series

1. In Depth (2019), Measure of Dispersion Series

2. Diego and Mary (2019), Ascension series

3. Spectre (2019), Measure of Dispersion series

4. Computer Love (2019), Measure of Dispersion series

Written by:

Daniel Gauss is, a native of Chicago, brings a unique perspective to the art world through his thoughtful critiques and community-focused ethos. A graduate of the University of Wisconsin (BA) and Columbia University (MA), Daniel has spent his adult life dedicated to education and social services, choosing a path of service over the profit-driven corporate world. Now based in New York City, Daniel applies his rich background to his work as an art critic, offering nuanced insights that reflect his deep understanding of culture, history, and human connection. Over the years, he has contributed to prominent art platforms such as Hyperallergic, ArtForum, and ArtNet News. Known for his articulate writing and keen ability to uncover the social narratives within art, Gauss often highlights works that challenge societal norms or amplify underrepresented voices. In addition to his writing, he remains committed to community engagement, volunteering with local organizations and mentoring aspiring creatives.

words / Jennifer Inacio

The55project:

(Miami - 2020)

Jennifer Inacio:

Okay, perfect. Okay, so I think we can start.

Thank you, everyone.

and thank you Gustavo for being here today. We're really excited with the project that opens tomorrow to the public at three o'clock

We'll have a members preview at two. And before we start, I just want to let everyone know

Just one second. Oh, I'm sorry, I'm getting a message here.

Jennifer Inacio:

Okay, perfect. So before we start, I just wanted to thank all the sponsors we have: the Consulado Geral do Brasil here in Miami. They're great supporters of the 55 project, and Plus Interior design, Five Drinks Company, Miami-Dade County, Culture Built Florida Miami Beach, and of course, Miami Beach Botanical Gardens, because they are collaborating with the 55 project.

And for those of you who might not know, We're here on the 55 project Instagram. I strongly suggest people explore and see what this project does. It's a great initiative to bring Brazilian artists and promote Brazilian artists here in the US, with a focus here in Miami and also New York. So, I’ve been fortunate to work a lot with, with Flavia and Maria and everyone who was and is still involved with the program.

So we're glad to be here today with Gustavo Prado, Brazilian artists, but based in New York. And I will skip the formalities of bios and just dive straight into the conversation. And anyone who has questions throughout the conversation, just feel free to drop them into the comment section below, and I'll try to catch them, or maybe at the end, I'll just go and review everything.

So Gustavo, let's start talking about the project here and how it all started, because it is an iteration or different versions of other projects that you have done in the past.

The undercurrent is a project here in Miami,"Measures of Dispersions" has been a project or a series of not just public art, but, sculptures and other works that you create using these convex mirrors that we see. So talk a little bit about how different it's been from these other series and similarities too, because I think the materials are very (..) are always the same, but put in different contexts. So tell us.

Gustavo Prado:

So let me just thank you, Jennifer, Flavia, and everyone at the project 55 in the Miami Beach Botanical Garden. I’m Really happy to be doing this project in Miami right now. It's odd because from the beginning, when I started to work with this system of sculptures of almost like this machine of generating different projects and sculptures. It was always planned to be able to be sourced anywhere it went. So whenever I was invited or was doing like a proposal to do a new project, I could get the materials from that location, right? So these are out of shelf materials, which is a term that we use here for things that you can find in any hardware store or, you know (...) they're very common things. They're part of the city and the way that the city is built and organized. So it's interesting that in a year when I'm stuck in a studio in New York, the work still going around, and it's able to see things, that from the studio here I'm not able to see. I've had that experience before, even through platform, search, Instagram, of having placed a work somewhere, and then have people and even in a different city in the world [interacting]. And when the first edition, like the first version of this project happened in Rio at the Botanical Garden, people would make selfies and be there and post their pictures online, on Instagram and tag me, and I'll be able to see how the weather is in Rio, if it's sunny or rainy. So have this experience of a completely different place from New York. So you have those two aspects, that the way that the materials and the way of building the work was conceived, and the way that I first planned for it, which is this way of not having to fabricate anything, and I'm combining things that are already in circulation, that are already available. So that was the strategy for be able to do larger public sculptures without much resource, and at the same time you have that aspect of challenging people to see a material there, think that they are familiar with in a new way. I think that was always the challenge with sculptures. So you reveal something about the material that hasn't been revealed before. You review something about that space in which the sculpture is placed, or an installation is placed that you haven't thought of before. So I feel like this piece of the Miami Botanical Garden, it's like the maturing of like several things that I plan. And that I prepare for, but you're being put to the test at this project, to do a public sculpture without being able to be present at the space where it's being built and in seen. And it's, it's interesting, it's a challenge…

Jennifer Inacio:

and I was gonna ask, this is good, because I was one of my questions I wanted to ask you, is that I think now a lot of especially with the quarantining, I think now it seems we're going to go back into some lockdowns in some cities. So I think when institutions and galleries started to reopening, (...) i know from where I've worked, where i work we're thinking about, outside. I think the outside is definitely something that you feel safer now, and it's interesting to see actually, here in Miami, there are a couple of institutions, galleries and museums, thinking more about this outside public space in order to still cater and present and offer art when people might not feel safe going inside. How do you feel? how does this that play? You know it's it's good to you because it's good for you, because you're already thinking in this sense and thinking about public art. But does that change in any way how you had been thinking lately about works? This new dynamic of presenting works safely to viewers, depending on where we'll be, if we'll be in a new lockdown soon or and or not. You know, so has that affected you in thinking that way?

Gustavo Prado:

Yeah, absolutely.

I think that gardens, even at the Miami Botanical Garden, where you have, like a Zen, Japanese garden, right? Gardens have always been a space where you invited to go to, not to escape your thoughts or worries or concerns, but mostly, it's like an invitation to relate with something that's outside of yourself, right? Like you focus on a pond, you focus on a tree. And I feel it's not that we inside our own spaces and homes, and is that we are also trapped mentally in terms of being concerned about, are we going to have a vaccine? And when is it going to come? What's the political situation and all that was an election (...). So it's not that we're trapped, just physically. We're trapped psychologically, mentally. So art was always that invitation of coming outside of yourself sometimes to have a political conversation and have that, that way of seeing something that has political content through a new light. But there's also that freeing experience of just escaping a narrative, having something that's physical and present in the world that allows you to get out of that narrative. So I feel like this kind of public art, and public art in general is very important, like, maybe more than ever. Like, I have just been through an experience of going through a residency here in New York, where a lot of other Brazilian artists have participated in, and one of the gifts of the of the residency was to be able to work in the garden, and to have this system where we're being dialog with the way that space is always changing.

So that's also some like part of the of the challenge of working with mirrors, working from a distance, is that you from the get go, you acknowledge that you're not in complete control of everything that's going to happen. You build a work to be in flow, in flow with that space, in flow with the people that are going to join you in that space. So there's that sense of an invitation, as I was saying, like a garden has always been.

I'm just interested in, especially in this occasion, when you have a work that's been traveling, almost like a troupe or a music show that you go from one city to the next, it's interesting to have that experience of a sculpture that or a project that through its relationship with the origin with the Botanical Garden in Rio, created enough situations and complexities that you'll be able to carry to a new garden, to a new botanical garden, and to see how it's going to relate with that space. And we've made several changes for that new space that has a different scale, that has different kinds of plants, but definitely that sense of like inviting people to come outside, but to come outside not just of their physical spaces, and join a lot larger group of people safely with their masks in this new space, but to come outside of their thoughts, to come up outside of their inner narrative, of their of their inner concerns.

Jennifer Inacio:

And I think this relates a lot to what you're doing with the work psychology, philosophically, even with the title too. We talked a lot about, how this work, the reflections are not just a public work or sculpture that you just walk through and look at it. It's really making you think about new ways of looking, or new alternatives…

So it's interesting. You bring that point, because i was writing the text for for the exhibition I mentioned that (...), and we talked about this, like these new sidelines, by creating these sculptures, or these passageways with the works, with these reflective sculptures that are pointing, or the reflection changes not, not just based on the angle that you, you are, intervening and creating, but also the public. The public is creating that experience as well, by the way that they move, if they move fast, if they, look at a different angle or, or if they approach the distance to is also a factor. So maybe we can talk a little bit about the title and how this relates to exactly what you're saying, coming outside of like, mentally, even to escape this, this world that we are blocked physically and mentally, but also offering new alternatives of seeing things and seeing your surroundings, not just physically but also mentally.

Gustavo Prado:

Yeah, I love when you brought up that concept of sideline and all that. It came to mind that when I was a kid, I had this way of thinking like an explorer or adventure that goes to the Himalayas for climbing a mountain for the first time, and that sort of experience. I always thought of that from the point of view of: so he's seen something that nobody else had seen before. He's seen the world from a position, from an angle that nobody else has seen before. And when you think about the history of mirrors and lenses, it has always been in relationship to that urge, that kind of hunger, that kind of desire that exists in terms of being hungry with the eyes, like wanting to see something in a way that nobody has seen before, and from a place that nobody even when you think about sci fi, science fiction, that sort of thing, like you see a planet, it has two moons or three moons, you've seen something that nobody else had seen before. So it's interesting that idea on the current kind of relates to the potential that exists in every place to be seen for the first time. There's a way of seeing that same place for the first time, because it's always changing, but because there's a person that's seen it, that's different. There's a configuration, a combination of elements that's going to be seen in a different line, in a different way, and you have the symbolical aspect of it, but also the physical, the perceptual aspect of it.

So I think when artists began to use lenses, you begin you can see it as revealing something of the world for the first time, an aspect of the world like that has not have not been revealed before. But you can also think of it as inaugurating or creating a completely new world, like when Vermeer, was using lenses, he created a completely new way of doing painting. So I think that we are always after that undercurrent, that kind of underground river, or of potentiality for what can be seen or what can be experienced of the world.

This is almost like squeezing out of it another job of some of an experience that you haven't had before. So I'm sure that the Botanical Garden is a very popular place in Miami, and a lot of people have been through it. And when you're invited to do a public piece there there's that challenge, can I relate to that space? Or can I review something about that space? Can I offer an experience of it and with it? Right? It's not just placing something there. Is like there's a desire to reveal something about it in dialogue with it that hasn't been revealed before. So, yes, I think that's also that level of humility, you know that you're like creating the elements to have the garden itself, be the protagonist, and even the viewer be the protagonist, because the work is going to exist in their eyes depending on how long they want to expand, they want to spend there, how much they want to explore of it. What is their availability for it?…

The55project:

The Undercurrent

(Miami - 2020)

Jennifer Inacio:

Okay, perfect. Okay, so I think we can start.

Thank you, everyone.

and thank you Gustavo for being here today. We're really excited with the project that opens tomorrow to the public at three o'clock

We'll have a members preview at two. And before we start, I just want to let everyone know

Just one second. Oh, I'm sorry, I'm getting a message here.

Jennifer Inacio:

Okay, perfect. So before we start, I just wanted to thank all the sponsors we have: the Consulado Geral do Brasil here in Miami. They're great supporters of the 55 project, and Plus Interior design, Five Drinks Company, Miami-Dade County, Culture Built Florida Miami Beach, and of course, Miami Beach Botanical Gardens, because they are collaborating with the 55 project.

And for those of you who might not know, We're here on the 55 project Instagram. I strongly suggest people explore and see what this project does. It's a great initiative to bring Brazilian artists and promote Brazilian artists here in the US, with a focus here in Miami and also New York. So, I’ve been fortunate to work a lot with, with Flavia and Maria and everyone who was and is still involved with the program.

So we're glad to be here today with Gustavo Prado, Brazilian artists, but based in New York. And I will skip the formalities of bios and just dive straight into the conversation. And anyone who has questions throughout the conversation, just feel free to drop them into the comment section below, and I'll try to catch them, or maybe at the end, I'll just go and review everything.

So Gustavo, let's start talking about the project here and how it all started, because it is an iteration or different versions of other projects that you have done in the past.

The undercurrent is a project here in Miami,"Measures of Dispersions" has been a project or a series of not just public art, but, sculptures and other works that you create using these convex mirrors that we see. So talk a little bit about how different it's been from these other series and similarities too, because I think the materials are very (..) are always the same, but put in different contexts. So tell us.

Gustavo Prado:

So let me just thank you, Jennifer, Flavia, and everyone at the project 55 in the Miami Beach Botanical Garden. I’m Really happy to be doing this project in Miami right now. It's odd because from the beginning, when I started to work with this system of sculptures of almost like this machine of generating different projects and sculptures. It was always planned to be able to be sourced anywhere it went. So whenever I was invited or was doing like a proposal to do a new project, I could get the materials from that location, right? So these are out of shelf materials, which is a term that we use here for things that you can find in any hardware store or, you know (...) they're very common things. They're part of the city and the way that the city is built and organized. So it's interesting that in a year when I'm stuck in a studio in New York, the work still going around, and it's able to see things, that from the studio here I'm not able to see. I've had that experience before, even through platform, search, Instagram, of having placed a work somewhere, and then have people and even in a different city in the world [interacting]. And when the first edition, like the first version of this project happened in Rio at the Botanical Garden, people would make selfies and be there and post their pictures online, on Instagram and tag me, and I'll be able to see how the weather is in Rio, if it's sunny or rainy. So have this experience of a completely different place from New York. So you have those two aspects, that the way that the materials and the way of building the work was conceived, and the way that I first planned for it, which is this way of not having to fabricate anything, and I'm combining things that are already in circulation, that are already available. So that was the strategy for be able to do larger public sculptures without much resource, and at the same time you have that aspect of challenging people to see a material there, think that they are familiar with in a new way. I think that was always the challenge with sculptures. So you reveal something about the material that hasn't been revealed before. You review something about that space in which the sculpture is placed, or an installation is placed that you haven't thought of before. So I feel like this piece of the Miami Botanical Garden, it's like the maturing of like several things that I plan. And that I prepare for, but you're being put to the test at this project, to do a public sculpture without being able to be present at the space where it's being built and in seen. And it's, it's interesting, it's a challenge…

Jennifer Inacio:

and I was gonna ask, this is good, because I was one of my questions I wanted to ask you, is that I think now a lot of especially with the quarantining, I think now it seems we're going to go back into some lockdowns in some cities. So I think when institutions and galleries started to reopening, (...) i know from where I've worked, where i work we're thinking about, outside. I think the outside is definitely something that you feel safer now, and it's interesting to see actually, here in Miami, there are a couple of institutions, galleries and museums, thinking more about this outside public space in order to still cater and present and offer art when people might not feel safe going inside. How do you feel? how does this that play? You know it's it's good to you because it's good for you, because you're already thinking in this sense and thinking about public art. But does that change in any way how you had been thinking lately about works? This new dynamic of presenting works safely to viewers, depending on where we'll be, if we'll be in a new lockdown soon or and or not. You know, so has that affected you in thinking that way?

Gustavo Prado:

Yeah, absolutely.

I think that gardens, even at the Miami Botanical Garden, where you have, like a Zen, Japanese garden, right? Gardens have always been a space where you invited to go to, not to escape your thoughts or worries or concerns, but mostly, it's like an invitation to relate with something that's outside of yourself, right? Like you focus on a pond, you focus on a tree. And I feel it's not that we inside our own spaces and homes, and is that we are also trapped mentally in terms of being concerned about, are we going to have a vaccine? And when is it going to come? What's the political situation and all that was an election (...). So it's not that we're trapped, just physically. We're trapped psychologically, mentally. So art was always that invitation of coming outside of yourself sometimes to have a political conversation and have that, that way of seeing something that has political content through a new light. But there's also that freeing experience of just escaping a narrative, having something that's physical and present in the world that allows you to get out of that narrative. So I feel like this kind of public art, and public art in general is very important, like, maybe more than ever. Like, I have just been through an experience of going through a residency here in New York, where a lot of other Brazilian artists have participated in, and one of the gifts of the of the residency was to be able to work in the garden, and to have this system where we're being dialog with the way that space is always changing.

So that's also some like part of the of the challenge of working with mirrors, working from a distance, is that you from the get go, you acknowledge that you're not in complete control of everything that's going to happen. You build a work to be in flow, in flow with that space, in flow with the people that are going to join you in that space. So there's that sense of an invitation, as I was saying, like a garden has always been.

I'm just interested in, especially in this occasion, when you have a work that's been traveling, almost like a troupe or a music show that you go from one city to the next, it's interesting to have that experience of a sculpture that or a project that through its relationship with the origin with the Botanical Garden in Rio, created enough situations and complexities that you'll be able to carry to a new garden, to a new botanical garden, and to see how it's going to relate with that space. And we've made several changes for that new space that has a different scale, that has different kinds of plants, but definitely that sense of like inviting people to come outside, but to come outside not just of their physical spaces, and join a lot larger group of people safely with their masks in this new space, but to come outside of their thoughts, to come up outside of their inner narrative, of their of their inner concerns.

Jennifer Inacio:

And I think this relates a lot to what you're doing with the work psychology, philosophically, even with the title too. We talked a lot about, how this work, the reflections are not just a public work or sculpture that you just walk through and look at it. It's really making you think about new ways of looking, or new alternatives…

So it's interesting. You bring that point, because i was writing the text for for the exhibition I mentioned that (...), and we talked about this, like these new sidelines, by creating these sculptures, or these passageways with the works, with these reflective sculptures that are pointing, or the reflection changes not, not just based on the angle that you, you are, intervening and creating, but also the public. The public is creating that experience as well, by the way that they move, if they move fast, if they, look at a different angle or, or if they approach the distance to is also a factor. So maybe we can talk a little bit about the title and how this relates to exactly what you're saying, coming outside of like, mentally, even to escape this, this world that we are blocked physically and mentally, but also offering new alternatives of seeing things and seeing your surroundings, not just physically but also mentally.

Gustavo Prado:

Yeah, I love when you brought up that concept of sideline and all that. It came to mind that when I was a kid, I had this way of thinking like an explorer or adventure that goes to the Himalayas for climbing a mountain for the first time, and that sort of experience. I always thought of that from the point of view of: so he's seen something that nobody else had seen before. He's seen the world from a position, from an angle that nobody else has seen before. And when you think about the history of mirrors and lenses, it has always been in relationship to that urge, that kind of hunger, that kind of desire that exists in terms of being hungry with the eyes, like wanting to see something in a way that nobody has seen before, and from a place that nobody even when you think about sci fi, science fiction, that sort of thing, like you see a planet, it has two moons or three moons, you've seen something that nobody else had seen before. So it's interesting that idea on the current kind of relates to the potential that exists in every place to be seen for the first time. There's a way of seeing that same place for the first time, because it's always changing, but because there's a person that's seen it, that's different. There's a configuration, a combination of elements that's going to be seen in a different line, in a different way, and you have the symbolical aspect of it, but also the physical, the perceptual aspect of it.

So I think when artists began to use lenses, you begin you can see it as revealing something of the world for the first time, an aspect of the world like that has not have not been revealed before. But you can also think of it as inaugurating or creating a completely new world, like when Vermeer, was using lenses, he created a completely new way of doing painting. So I think that we are always after that undercurrent, that kind of underground river, or of potentiality for what can be seen or what can be experienced of the world.

This is almost like squeezing out of it another job of some of an experience that you haven't had before. So I'm sure that the Botanical Garden is a very popular place in Miami, and a lot of people have been through it. And when you're invited to do a public piece there there's that challenge, can I relate to that space? Or can I review something about that space? Can I offer an experience of it and with it? Right? It's not just placing something there. Is like there's a desire to reveal something about it in dialogue with it that hasn't been revealed before. So, yes, I think that's also that level of humility, you know that you're like creating the elements to have the garden itself, be the protagonist, and even the viewer be the protagonist, because the work is going to exist in their eyes depending on how long they want to expand, they want to spend there, how much they want to explore of it. What is their availability for it?…

Jennifer Inacio:

Are you working on anything now? at the moment I know we're just working on this project. But do you have any projects or any ideas that you can share with us? Or, what is your method of thinking of new things and new projects out there?

Gustavo:

I think there are things happening in parallel, like, I'm still very much devoted to this series of (..) in terms of the private experience in the studio, I'm very much devoted to research in this Lego series, this Ascension series, but in terms of public art, there's also, like, several projects happening. And the project that I was and still I am, most excited about, is the possibility of doing a permanent piece for the City of Vancouver.

I was invited by Marcelo Dantas, curator that worked with a way Ai Weiwei and so many others, such a brilliant figure. We first worked in Rio, there's still a permanent piece that we did together for space in Rio at FIRJAN that has a really strong relationship with this piece at Miami.

So we were first thinking of doing something for the for the Vancouver Biennial, but at a certain stage of the project, it became a project for the city that will stay in the city. I'm also doing a project for Ohio, and in that sense, it's very interesting to cross over to like architecture concerns. So in Ohio, is also a part of the city that's being renewed, of one city in Ohio that's being renewed, and so they putting art at the center of that new portion of the city. So as the as this little strategy of our shelf material starts to grow and grow and which was at the beginning, a kind of one like rebellious and immature attempt of hitting [Richard] Serra in the gut because I was writing about Richard Serra at the at the time, it was kind of irritated by the kind of strength and power that you need to have to be able to mobilize that much energy.

So what became in the beginning this rebellious, immature kind of strategy. Now it's like: okay, now I'm beginning to have to put it to the test, because it's gaining scale, and it's starting to become this thing that in the city needs to hold its own, it needs to last and relate to all kinds of other complexities and social structures. And it's not just formal solutions. It's like what it's going to do for the space that it's being placed at. So it's interesting to be doing all of that, from being in New York. We were going to do the project recovering in March, and then they closed the border, so I couldn't go. So we're going to do it next year. But the Ohio I'm developing everything from the studio, Miami too, so I just did a piece in Rio that was also done in that way. So yeah, I putting the system to the challenge and to the test.

But yeah, exciting times…

I hope I can go to Miami soon, yes, for the project also, because it's getting very cold in New York and I would love to go to Miami

Jennifer Inacio:

No, this is, yeah, this is this, I think, from December to March anytime at the museum where I work at, we would have to invite artists from New York or from colder places. It was always easy to get people here, because they’re trying to run away.

Gustavo Prado:

No, I remember I was at the Perez Museum and I saw those beautiful, plants hanging from there, it's like, how did they maintain this, yeah, and it's like, how did they maintain it? Wow, they have amazing weather. Oh, yeah it's a challenge. I'm sure it is. But there's also that aspect of a place that allows for that to grow and to live.

Jennifer Inacio:

And how is it, being from Brazil and living in New York? It's an amazing city, but you've been there for a couple of years, right? But I know that when I went to — going off topic here, but I think it's interesting to hear —, there was a Brazilian living in New York, and I know when I went to study abroad, I went to Europe, the weather, the lack of sun. At four or five o'clock it's already dark. I mean, it's getting darker here earlier too. But besides, being exposed to amazing art, like, how is it (...)

Gustavo Prado:

well, that was always the point, right?

To be closer to all that art that when I visited New York I remember that when you're in Rio, you want to be close to Arpoador and Ipanema, like, so that's that experience. But here, I wanted to be close to those works, but there's also, like, a very important aspect of it, because we always think of like something being exotic, as something being tropical or south of the equator. And the word, the word itself, doesn't mean that it depends on context. It depends on who finds it exotic or not. So it depends on the place that you come from. So for me, when I arrived in New York, the bridges and the way that they are built, and this modular systems and this abundance of materials that you can enter in a hardware store and can find a whole universe of things with which you can build that was so exotic, you know? And then the way that even the landscape here is, I remember that I was photographing obsessively. And I remember a conversation with my brother, and he was like: What is with all the photographs? And I was like, maybe photographing is a way of becoming familiar with this place faster. I still see it as a foreign, alien space. Not so much anymore. Like it's weird how you become familiarized and it becomes kind of the standard after a few years, and you kind of lose that first punch of energy that you get from when you arrive in a new space, right? You see like that's very common place to say that artists, writers, musicians, have always traveled to other cities to become that more creative and challenged by that sense of uncertainty, and becoming unfamiliar with the place in order to become creative. So that was very present for me but I was very amazed by by those ways of building, that those even the how democratic it is(...)

Because in Brazil, we have that sense of, like, there's going to be people around workers and so they're going to be like, cheap labor, and they're going to level the concrete. So I'm going to be this genius that does this curves and not criticizing the designs or the architecture of the empire.

But I'm just saying there's a social context that allows for that to be built and this massive quantity of people that are going to just migrate to the center of the country to do the concrete curve that I want with my drawing so, and here you have that kind of Bauhaus thing, like i'm going to come up with the modular system that anybody's going to be able to assemble and put together, and it's, it's going to be very flexible, because from just one point, I'm going to be able to project a lot of weight, so even ideologically and politically, not just in terms of that being very exotic to me, but that, that concept of Oh, so I can just use this to be whatever I want, which is the same kind of thinking with Legos, right? That the system was pre designed for and those systems gave me the independence to build work without relying on those much, those resources, because they have this also this democratic thinking about them. So, yeah, I mean, that was from the beginning, a very strong input of energy. But I gotta tell you, I miss the people. I miss the conversations, I miss the relationships. I miss the studios of my friends. There's like right next to my piece, there's a piece by a very dear friend, Raul Mourão, we did so many good things together here in New York before he moved back to Brazil, but he's always here still, and so I miss the conversations. There's so much part of the work… right?

Jennifer Inacio:

Yeah, the conversations definitely help. But I think now with people getting more used to digital it's not the same, obviously. But I know I talked to my friends in zoom more than I would see them before.

So I think that, I think we're running out of time, though. I just wanted to answer one question here real quick. How can we see the Miami Project Online? I don't know if Flavia has any suggestions, because it is an outdoor space. It might be feel safer, but if you still don't feel safe, I'm sure Flavia and people from the 55 project will take amazing photographs to have it online and accessible. So. The opening is tomorrow at two for members and to the public at three, I just don't want to get cut. So thank you so much. Gustavo and everyone, all the sponsors for supporting this project.

Gustavo Prado:

Thank you Jeniffer, Flavia, and Cristina Mascarenhas is such a good friend that supported this project as well. I'm super excited, couldn't be more excited, thank you all so much.