words / Saul Ostrow

Photographs of a section of sky framed by buildings, others of dented car fenders with broken headlights, bundles found on the street that are unrecognizable as people, modular assemblages of readymade parts: prominently mirrors. This is brief inventory of Gustavo Prado’s recent works. What it does not reveal is that each work is in turn, a complex aggregate of ideas about the temporal and spatial – the ideal and the abject — about cognition and comprehension. Each work is self-conflicted, rift with contradictions. Each group of works in turn initially seems to be disconnected from the other — as such collectively, they seem at first to be about everything all at once, and nothing in particular. It is therefore our task to focus them, limit their potentiality and come to make sense of each and the whole.

Prado’s restless movement from meaning to sense, from intention to indirectness reflects the influence of a contemporary, post-Modernism that responds not only to the collapse of Modernism’s utopian ideals and rationalism, but also to the dystopian vision of 1980s Post-Modernism, which was premised on simulation, replication, and spectacle. By occupying neither one or the other position, Prado pits one against the other producing uncertainty and attentiveness. He in a non-hierarchical — non-historical manner subverts the limitations of the art object as a conveyance of meaning. For instance, what he presents are assemblages of either common events, or in the case of the mirror pieces — cheap mass produced materials that are pragmatically combined to diverge from their intended purpose, as the surveillance and blind-spot mirrors, which are to be found in the subway, shops, and on the streets. As is the nature of assemblages their components simultaneously retain their identity while lending some of its qualities to the greater whole. So while his works may initially appear to be idealized and abstract, they are in all-ways mundane: in this context Prado uses the art object as a means both of self-reflection and conveyance.

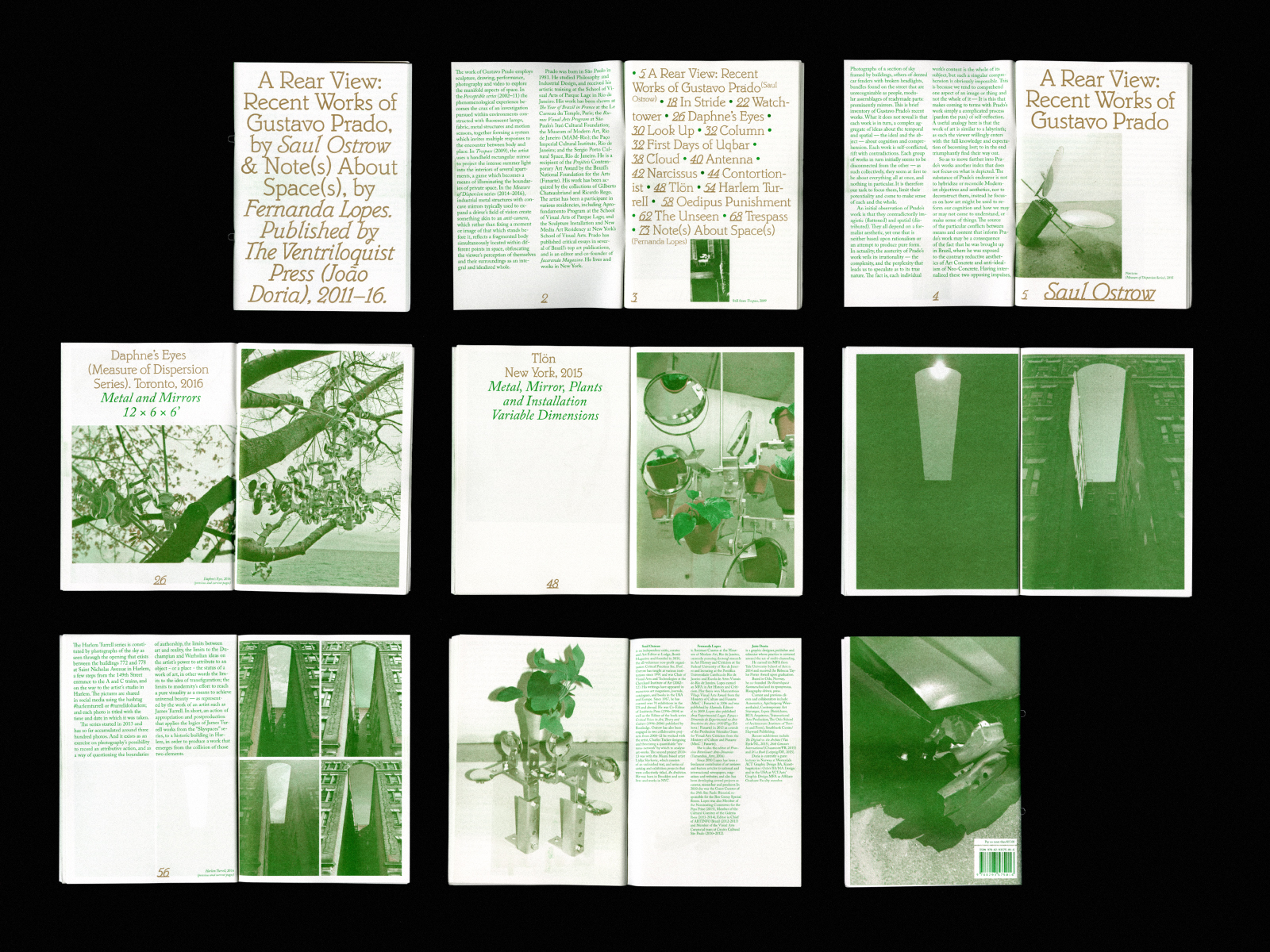

A Rear View: Recent Work of Gustavo Prado

(2016)

Photographs of a section of sky framed by buildings, others of dented car fenders with broken headlights, bundles found on the street that are unrecognizable as people, modular assemblages of readymade parts: prominently mirrors. This is brief inventory of Gustavo Prado’s recent works. What it does not reveal is that each work is in turn, a complex aggregate of ideas about the temporal and spatial – the ideal and the abject — about cognition and comprehension. Each work is self-conflicted, rift with contradictions. Each group of works in turn initially seems to be disconnected from the other — as such collectively, they seem at first to be about everything all at once, and nothing in particular. It is therefore our task to focus them, limit their potentiality and come to make sense of each and the whole.

An initial observation of Prado’s work is that they contradictorily imagistic (flattened) and spatial (distributed). They all depend on a formalist aesthetic, yet one that is neither based upon rationalism or an attempt to produce pure form. In actuality, the austerity of Prado’s work veils its irrationality— the complexity, and the perplexity that leads us to speculate as to its true nature. The fact is, each individual work’s content is the whole of its subject, but such a singular comprehension is obviously impossible. This is because we tend to comprehend one aspect of an image or thing and not the whole of it — It is this that makes coming to terms with Prado’s work simply a complicated process (pardon the pun) of self-reflection. A useful analogy here is that the work of art is similar to a labyrinth; as such the viewer willingly enters with the full knowledge and expectation of becoming lost; to in the end triumphantly find their way out.

So as to move further into Prado’s works another index that does not focus on what is depicted. The substance of Prado’s endeavor is not to hybridize or reconcile Modernist objectives and aesthetics, nor to deconstruct them, instead he focuses on how art might be used to re-form our cognition and how we may or may not come to understand, or make sense of things. The source of the particular conflicts between means and content that inform Prado’s work may be a consequence of the fact that he was brought up in Brazil, where he was exposed to the contrary reductive aesthetics of Art Concrete and anti-idealism of Neo-Concrete. Having internalized these two opposing impulses, Prado’s works are alternately purist and mundane, transcendent and commonplace. For instance, the photos that make up Harlem Turrell are minimalist and beautiful, yet they consist of little more than a coffin shaped section of the sky framed by apartment buildings – The contained area is sometimes flat grey, blue or with fluffy white clouds, etc.

But there is more to Harlem Turrell than some gesture mean t to aestheticize a section of sky., 300+ photographs presently make-up this work. This may leads us to ask; who orders their life so they can on a regular basis take photographs of some chance place, which reminds them of a James Turrell installation. It is not the sky, or the unobserved moments that Prado documents or calls our attention to, it is the multiple contexts within which this work exists — from photography’s documentary tradition to the sensuous aesthetic of transcendentalism. Viewers join the artist in believing that these photographs are meaningful, if seen through whatever index of their choosing. Subsequently they form an archive whose content is understood phenomenologically, cognitively, aesthetically, culturally and even politically. Within these various frameworks the repetitions and variations that these photographs record rather than being redundant come to make still some other sense.

A still longer index would identify Prado’s work not only in accord with their imagery, media, inferences, and shared logics, but also his employment of duration, repetition, and variation as terms and conditions relative to the production of symbolic representations, as well as their presentation. Such a list includes: variability, eventfulness, object-less-ness, site/site-less-ness, deferral, discontinuity, cognition and comprehension, interiority and exteriority — things in kind — types — degree, etc. This list requires another of the potential forms by which these may be actualized would include: assemblages of assemblages, modularity, seriality, and the Readymade. Prado applies this still incomplete index to the range of media, strategies and subjects that he works with; this is the reason why, at first, his works appear to be disconnected from one another. Yet, when their structures and themes are compared rather than taken in isolation, it becomes apparent that Prado by moving back and forth between the literal and objective, the conceptual and practical asserts the indeterminacy of experience and meaning. By exposing the discontinuity, complexity and multiplicity of our realities, Prado works define the ‘space’ of art as one that is simultaneously mythic, symbolic, and real. It is from this that this essay takes its title, which too is intended to call up the multiplicity of contradictorily references that range from that of the warning on a rearview mirror: that objects may appear closer than they actually are, to the idea that the work of art that we view is always already moving away from us.

Prado’s restless movement from meaning to sense, from intention to indirectness reflects the influence of a contemporary, post-Modernism that responds not only to the collapse of Modernism’s utopian ideals and rationalism, but also to the dystopian vision of 1980s Post-Modernism, which was premised on simulation, replication, and spectacle. By occupying neither one or the other position, Prado pits one against the other producing uncertainty and attentiveness. He in a non-hierarchical — non-historical manner subverts the limitations of the art object as a conveyance of meaning. For instance, what he presents are assemblages of either common events, or in the case of the mirror pieces — cheap mass produced materials that are pragmatically combined to diverge from their intended purpose, as the surveillance and blind-spot mirrors, which are to be found in the subway, shops, and on the streets. As is the nature of assemblages their components simultaneously retain their identity while lending some of its qualities to the greater whole. So while his works may initially appear to be idealized and abstract, they are in all-ways mundane: in this context Prado uses the art object as a means both of self-reflection and conveyance.

Using images and situations that are familiar but do not readily conform to the known symbolism, Prado generates conditions that he believes will cause the spectators to feel acutely self-conscious of varied aspects of their existence. Constructed from the incidental — this non-hegemonic realm generates a state of otherness, which are neither here nor there, that is simultaneously physical and mental, such as the moment when we see ourselves in a mirror, or imagine the narrative behind some inexplicable incident such as that the image of a dented fender. One may conclude from this that Prado analogously finds art to be a space within which differences are affirmed and denied as both real and imagined — as both fixed and dynamic. Inversely, his work asserts that art is a real space within the world we live in, but it lies outside or beside most places. In this art may be thought of as forming a heterotopia — a place that operates by its own logic and reasoning. Consequently, though it is possible to indicate art’s location in reality as being that of the institution and the marketplace - even these spaces are defined by their own ecologies and logics. From this we might deduce that Prado’s ambition is to via art, extract from and insert into our world things and events that have few or no intelligible connections with one another so as to require us to comprehend them in a non-habitual manner. This space subsequently is one of constant vigilance for it requires attentiveness and engagement, and simultaneously the inverse: deferral and indifference.

Let us imagine we find ourselves among art works by various artists who have been asked to install works in the corridors of a new luxury apartment building that a real estate developer is seeking to promote. Prado installs his photographs of those invisible people who occupy what can only be seen as marginable spaces. Prado’s images with their pain, formalism, and historicity, in a gallery or museum space would be little more than yet another social document of indifference and desperation, but in these hallways each image becomes a specter, haunting that specific space – each encounter be a silent accusation. Let us then imagine these same images presented without commentary in a newspaper format that is distributed free and whose only text is an appeal for donations to help the homeless. Here his photographs become an appeal. These alternate, aesthetic and social practices implicitly come to exist side-by-side reflecting opposing paradigms, which mirror aspects of the real world whose reflections fracture into multiple realities, including those of differing and conflicting ideologies, objectives, practices and responses.

A still broader inventory would have to include Prado’s images and structures’ relations to the their implicit and explicit social and the political content or Everyday-life. This inventory would expose the fact that though he exploits structuralism’s ability to identify analogies between apparently different forms, he is not a structuralist – in that for him the shared norms that frame his works are impositions – that serve only as hindrances, which Prado seeks to clear away because they induce habits on the part of the viewer that both aestheticize and devalue the very things he would have us consider. The events he focuses on and articulates are used to evade the dominant structures, which would make his work, literary, aesthetic and therefore intelligible – turn them into being about this or that. Instead, within the structures and habits that constitute the norm, Prado finds the relations of power that bear upon and determine those a priori meanings and expectations that obscure the complexity of everyday events. In response to this, Prado deals with precarious relationships between form and content by creating ambiguous, though immediately recognizable situations, inducing a sense of uncertainty that provokes the viewer to reconcile the visual information with a multitude of unstable references, e.g. we see a homeless person who is no longer recognizable as human being and we immediately understand this as a social critique premised on humanist or moral notions yet, Prado’s aesthetic instead is meant to have us consider the question of how and why we come to that reading, and whether ethically do we have a similar response when we come upon these people in our world.

From a Deleuzean perspective — what Prado tries to articulate is: how every action and every event is an exchange that denotes the ebb and flow of power, with relevance to differing aspects of daily life, and subsequently what is the economy of de-humanization and objectification. The position his work takes relative to this economy is that of the horizontal axis — a position engagement — we see only that which is before us, rather than that of the vertical, which provides distance — and an overview. The horizontality of Prado works’ cuts across modes of representation, media-forms and subjects, likewise they cut through language, meaning, metaphor — instead, Prado seeks analogy and comprehensions built on the notion that these are all the contrasting phases of one and the same things eg. smooth and rough are both terms applicable to surfaces and motion.

The dismantling of dichotomies permits Prado to envision his work as marking out a trajectory that escapes the narrowness of a world built on polarities. Obviously, there are limits to the degree to which this reworking of rationality may be done and the affect that it may achieve; for instance, it cannot re-form modernity or our sense of being in totality– but it may cause us to reflect upon the complexity and unrealized potentiality of our own everyday endeavors, which we have been taught to think of as comprehensible contiguous events rather than a construct of fragments, gaps, and discontinuities. It is only our habits of thought that permit us creating aggregates , which result in objects that are then in turn negotiated, improvised, and navigated and made symbolically consistent resulting in a somewhat predictable real.

Based on his desire to intervene in the simulacra of the everyday and the world of objects, Prado’s work may be considered political, not in the usual sense of exposing some aspect of the economy of power or its abuse. Instead, he compels his audience to come to terms with an image-world that is constantly being ordered, framed, disassembled, and re-assembled for and by them. In this sense, Prado makes the conflict between the symbolic (the blindness of Oedipus) and the substantial (the damage caused by a crash) visible; this is the conflict between the object as document and as an objectification. Prado’s employs this differing states so as, to point to everything, including his own work. In this, he questioningly appropriates a wide range of unresolvable issues, such as: the boundaries of authorship, the aesthetic nature of reality, the semiotics of objects / places, the status of event or, the limits to the idea of transfiguration of the real, etc..

Still looking at Prado’s photo series Oedipus Punishment, a parallel can be drawn between the damaged headlights that can no longer light our way, and the blinding of Oedipus, who puts out his own eyes, providing us with still another inventory. The key here is that Prado biography, he had been brought up to understand that “the light” and truth are comparable. For Catholics “Truth” illuminates one’s way in the world — the truth is a thing that shines, gives light – revealing not only itself but also all that surrounds it. Symbolically, such awareness provides a greater chance of avoiding deception. In this context, we can connect how Prado has used light as both a subject and a medium – be it in his colored-light-filled-rooms and interactive environments, or in his current use of mirrors, photography, and video.

A less obvious inventory relative to the metaphorical and symbolic function of light and belief can be formulated here — its principle concerns are the conditions and terms of existence that originate with The Enlightenment. Since the 60s these master narratives have been the object of an extensive self-reflective critique. This index references the core of Western society’s operating system and that of Capitalism. It includes the secularization of such Christian notions as illumination, truth, essence, bare life, awareness, etc. These terms define human existence within the course of self-realization – cognitive development — awareness — which defines the process of transcendence and transformation. This process is a consequence of the needs, abstractions, and comprehension that come into being given our collective and individuated — public and private interaction with the external world, which is inclusive of people and things.

Underlying all of these indexes is the economy of bare life (bodies) and qualified life (one who may act). These terms designate the subject and object of social inclusion and exclusion (as defined by The Law). The key clue that these concepts are in play in Prado’s works is most apparent and obvious in the photo series the Unseen – which depicts those who have arrived at a state of bare life and are therefore almost unrecognizable as human beings. Though persistently striving to live – they appear to have become objects that are further objectified by being photographed. Those images make them present in absentia, while giving them recognition, yet they still exist without identity. So while the Unseen best illuminates and gives presence to this idea of the excluded (excepted), it also puts in an appearance in Prado’s mirror pieces for this address the idea again of privacy – the notion that one has a right to certain expectations. It is this existentially based system that Prado’s work disassembles, and de-structures, while using it contradictorily as an armature to generate dispersed of discontinuous objects/ categories/ situations.

The video Tresspass can be read within the context of the qualified life, as the inverse of the Unseen, it depicts people coming to their windows to shew away the artist, wanting him to stop recording their windows – in this moment, their windows become an interface between their public and private lives and the artist has become an intruder and a threat. Here, the qualified life becomes defined by an expectation of privacy — that is the idea they have the right to choose not to be seen because they participate in a social economy that permits them privacy. The mirror sculptures combine and confuse this notion of public exposure and privacy, for it permits an indirect observation. By looking into the array of rear-view and security mirrors, the viewer becomes invisible — that is, unseen, while the viewed is reduced to image/object. Within the resulting panopticon, viewers are led to believe they have a comprehensive view of their surroundings — yet in actuality the mirrors serve as lens that frame and exclude all that is outside the frame — in this the mirror pieces are not unlike the photographic works.

So now, we might add to Prado’s inventory the notion of distraction and extraction, as a corollary to interiority and exteriority, and to horizontality and verticality — these are not spatial terms here, instead they are relational ones. By emphasizing exchangeability, and multiplicity, Prado provides a framework for generating textual complexity. This economy is not stable and fixed; rather it is one in which successive complimentary and contradictory narratives displace and replace one another. This is not because the narratives are arbitrary — it is because no one narrative can tell the whole of the story that is given representation by Prado’s works. This is because each individual component tells its own tale and then also contributes to and modifies that of another. Each component exists as part of, and independent of the specifics of the work that they are deployed within; the task that the viewer is offered, is to engage coding, decoding, or recoding each component rather than to synthesize a whole, though they may insist on doing so.

Though not the final inventory, I will conclude with one that consists of 3 stages of a single process; these are the pre-cognitive (perception), the cognitive, and the act of recognition. The first is the realm in which the mind becomes aware of a stimulus — a process that is reflexive and chaotic. The second is the realm of concept development – the organization of the sensations that are the result of perception. The final is recognition; concept application — acts of recall in which the concepts that have been formulated are applied to each new situation, or encounter. This last stage consists of filters, shortcuts, and modes of behavior and thought that in effect order and limit our experiences — Recognition is the process within which things (all that is encountered or thought) comes to be comprehended based on whatever set of concepts that come to be (individually and collectively) applied to them. In a sense our comprehension of the world is a rearview — one that via memory looks back to past associations. This is why I have emphasized that the art-work as all other things comes to be understood only in parts, yetthe limitations our understanding places upon it does not affect its potentiality, or its complexity. In this context we may assert that Prado in recognition of this, has constructed his works so that the components that permit us to comprehend his works both physically and conceptually may be simultaneously, or sequentially connected, reconfigured, disconnected or inhibited.

Within the process of recognition nothing by virtue of its being is itself: nothing stands outside this system of differentiation and deferral. To apply this Derridean notion of différance to the work of art, the subject and content of the work can only reference a multiplicity of things (ideas, experiences, propositions), which in turn are mediated by the means of their conveyance and those of their reception, subsequently, some part (perhaps, most) of the thing is deferred. The viewer’s objectification fills in the resulting gaps and form an illusionary continuity and unity. In Lacanian terms, this is the realm of the symbolic — the space of power, order and discourse — the means by which the Real (that which occurs without reason of intent) is held in check. With this in mind, we can understand works that Prado produces as an exploration of representation (recognition) and as distinct from lived experience (cognition). Given this economy one may imagine that Prado finds value in the partiality of what may be transmitted, and the surplus it generates — From these paltry means Prado builds a model of how one may resist instrumentality, and remain a humanist without succumbing to idealism, or any apparent ideology.

Text for the Publication bellow:

Written by:

Saul Ostrow

is an independent critic, curator and Art Editor at Lodge, Bomb Magazine and founded in 2010, the all-volunteer non-profit organization Critical Practices Inc. Prof. Ostrow has taught at various institutions since 1991 and was Chair of Visual Arts and Technologies at the Cleveland Institute of Art (2002–12). His writings have appeared in numerous art magazines, journals, catalogues, and books in the USA and Europe. Since 1987, he has curated over 70 exhibitions in the US and abroad. He was Co-Editor of Lusitania Press (1996–2004) as well as the Editor of the book series Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture (1996–2006) published by Routledge. Ostrow has also been engaged in two collaborative projects. from 2008–12 he worked with the artist, Charles Tucker designing and theorizing a quantifiable “systems-network” by which to analyze art-works. The second project 2010–13 was with the Miami based artist Lidija Slavkovic, which consists of an unfinished text, and series of catalog and exhibition projects that were collectively titled, An Ambition. He was born in Brooklyn and now lives and works in NYC.