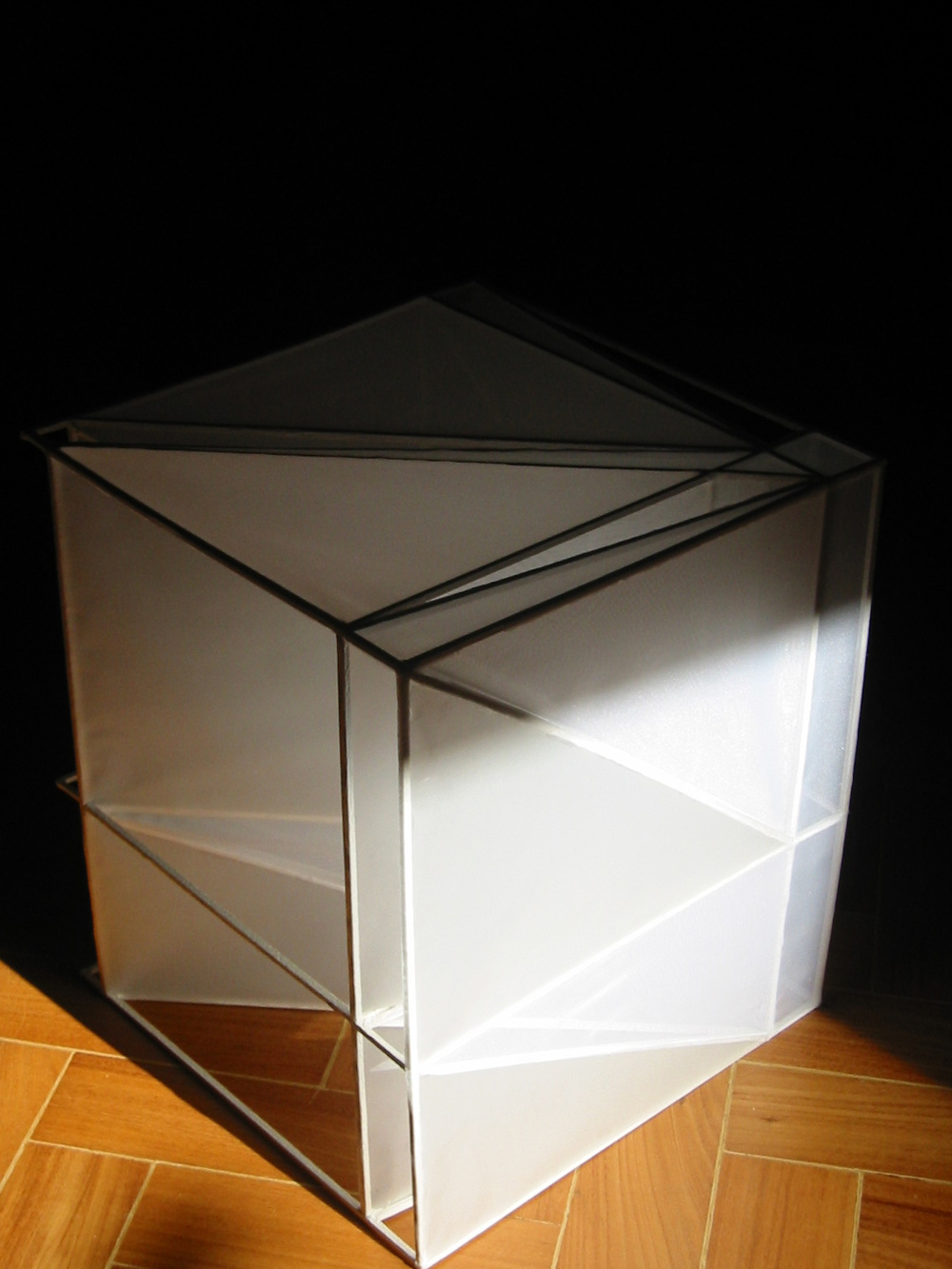

Perceptible Sun Clock

Wood and paper

51 x 51 x 51 cm (approx.)

20 x 20 x 20 in (approx.)

Rio de Janeiro, 2002

Sun Clock Perceptible (2002) was prepared to be an ever changing object. This is the first object produced for the “Perceptível” series, a series devoted to develop works that could serve as experiments to test the structures that underlay our ways of relating and perceiving objects. Using sculptures and installations, also as a way of analogously test the phenomenology concerns of philosophers like Merleau-Ponty, in this case, more specifically in the case of “Sun Clock” a way of representing the following problem posed by him: “How can anything ever present itself truly to us since its synthesis is never completed?”

For “Sun Clock” uses a cube, the more easily comprehensible volume, therefore, the more commonly used to organize space, to fragment it by creating directional vectors pointed to one of its dislocated axis, and by creating extra inner surfaces that look like passing pages of book. Other lines try to further fragment the integrity of its form and give it movement and complexity. The surfaces of this model/object are covered with fabric and paper that expect to receive sun light and that are prepared to react in different ways to it.

When the sun light moves around the object it changes it in complex ways making some areas translucent, others transparent, others opaque, and creating a ever moving and changing shadow on the floor right next to it, that further increases the perceptual fragmentation of the object, and accentuates the impossibility of completing a simplistic idea of how it appears.

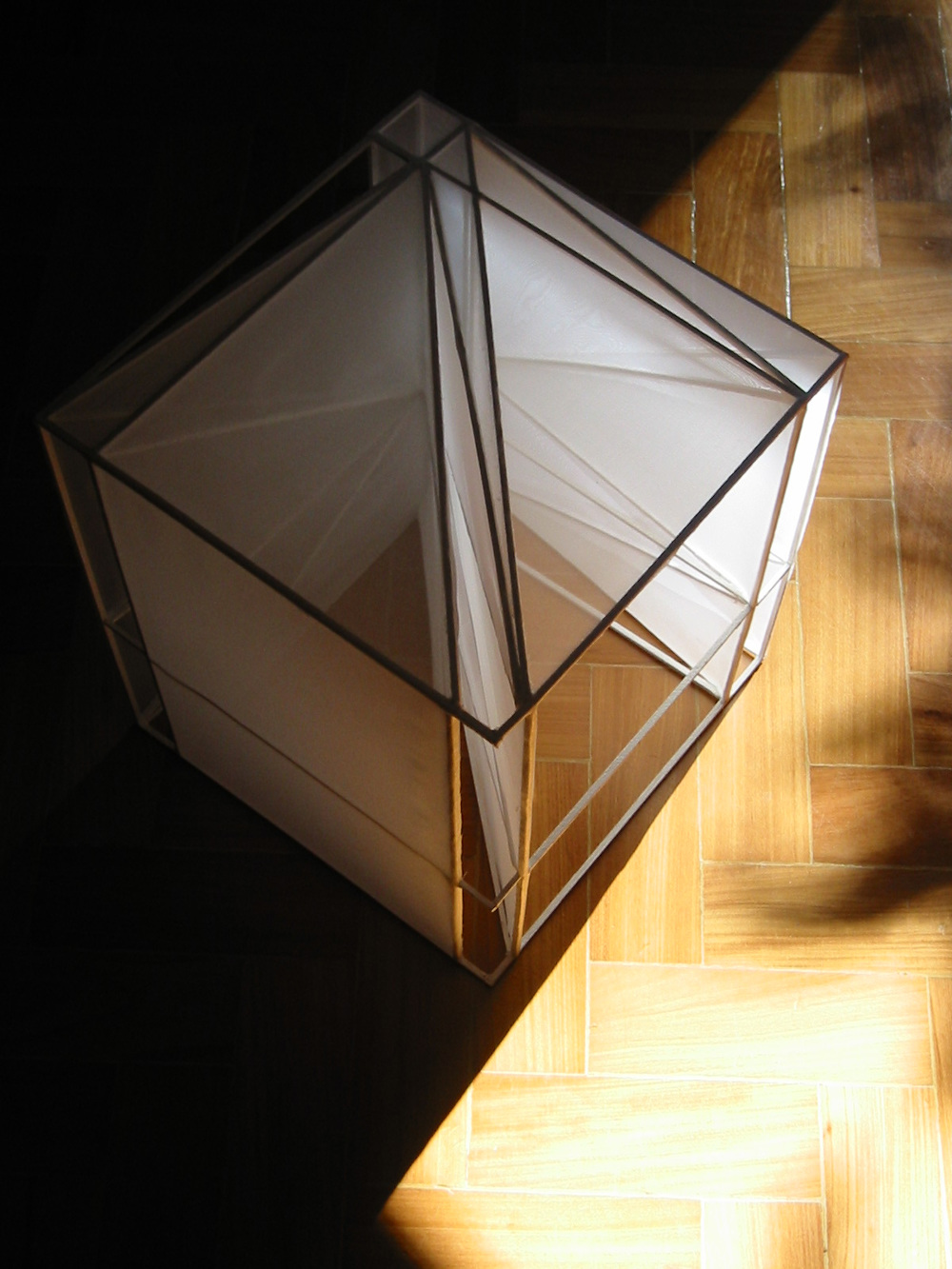

Wood and paper

51 x 51 x 51 cm (approx.)

20 x 20 x 20 in (approx.)

Rio de Janeiro, 2002

Sun Clock Perceptible (2002) was prepared to be an ever changing object. This is the first object produced for the “Perceptível” series, a series devoted to develop works that could serve as experiments to test the structures that underlay our ways of relating and perceiving objects. Using sculptures and installations, also as a way of analogously test the phenomenology concerns of philosophers like Merleau-Ponty, in this case, more specifically in the case of “Sun Clock” a way of representing the following problem posed by him: “How can anything ever present itself truly to us since its synthesis is never completed?”

For “Sun Clock” uses a cube, the more easily comprehensible volume, therefore, the more commonly used to organize space, to fragment it by creating directional vectors pointed to one of its dislocated axis, and by creating extra inner surfaces that look like passing pages of book. Other lines try to further fragment the integrity of its form and give it movement and complexity. The surfaces of this model/object are covered with fabric and paper that expect to receive sun light and that are prepared to react in different ways to it.

When the sun light moves around the object it changes it in complex ways making some areas translucent, others transparent, others opaque, and creating a ever moving and changing shadow on the floor right next to it, that further increases the perceptual fragmentation of the object, and accentuates the impossibility of completing a simplistic idea of how it appears.

Created over the course of 10 years (between 2002 and 2011), the Perceptible series followed and reflected significant changes in Gustavo Prado’s work, particularly regarding the viewer’s perception and the relationship between the artwork and space. Perceptible Sundial (2002) is the first work in the series and is presented as a cube (considered one of the simplest forms for human recognition), made with a wooden structure and covered with fabric and paper. Its relatively simple form becomes complex in its interaction with space (and time). Aspects such as the place where it is positioned, and the natural light that shines upon it (which changes throughout the day and from one day to the next), influence characteristics such as viewing angles, transparency, opacity, and shadows, making the perception of this work broad, varied, and almost unpredictable. It functions as a constant exercise in the viewer’s perception and the possibility of presence within space.

The following works in the series increasingly emphasize the installation dimension, expanding their scale in built environments with colored fluorescent lamps, fabrics, metal structures, presence sensors, and monitors. These are environments in which viewers are invited to be present, where external interferences are suspended, giving way to conditions of experimentation created and controlled by the artist, such as the use of color and the intensity of lighting, which directly affect the perception of space. Perceptible 8 (2005), for example, reproduces the form of Perceptible Sundial on an enlarged scale and, instead of relying on the sun, uses a set of lamps connected to the structure of the environment and presence sensors to shape the lighting of the space.

In the final works of the Perceptible series, the artist and the viewer engage with everyday space, outside the control and predictability of institutional spaces. This is the case with works like Perceptible Heraclitus River (2006). In this piece, a geometric structure was installed in different locations along a river in the city of Itaipava (a mountainous region of Rio de Janeiro). Over the course of 30 days, these situations were documented in photographs and videos, later edited into images that construct different perceptions from the presence of this object in a natural setting.

As a whole, the works in the Perceptible series draw attention to reality understood as a construction, always in progress—open, in process, and shaped by individual, political, social, and economic variables.