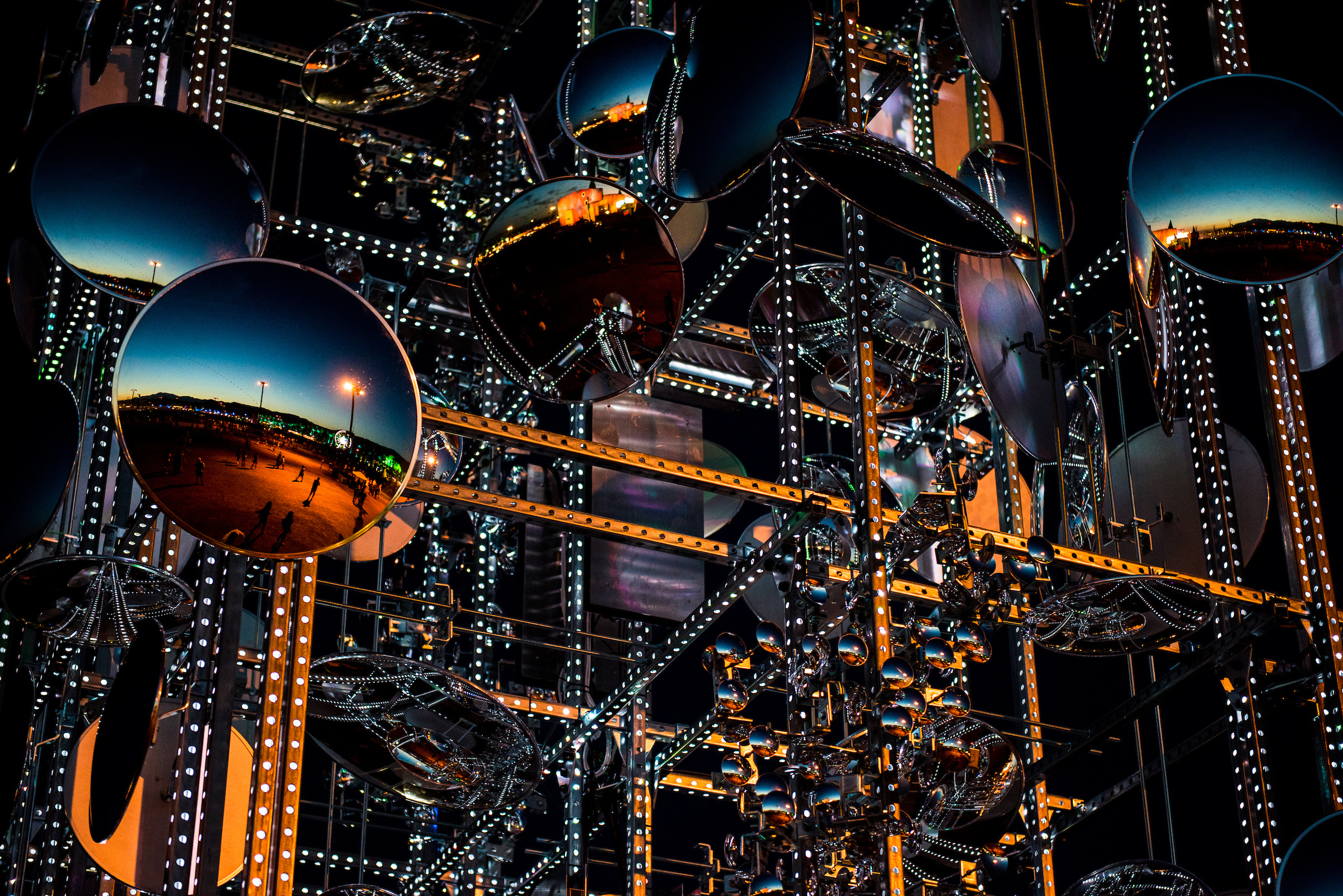

Lamp beside the golden door

Mirrors, metal, and LED lights

930 x 350 x 350 cm (approx.)

30x 11 x 11 ft (approx.)

Coachella Music Festival

Indio, California, 2017

Featured on:

1. Rolling Stone

2. Vogue

3. Architects News Paper

4. Artnet

5. Flaunt

6. LA Times

7. La Magazine

8. Design Boom

9. Grazia

10. Arch Daily

11. Art Infused

12. Popload

13. FFW

14. Nylon Magazine

15. Ilustrada - Folha de São Paulo

16. Uol

Interview with Francesca Fiorentini for

Coachella's Youtube channel.

Entrevista com Mila Burns para Globo Internacional.

Mirrors, metal, and LED lights

930 x 350 x 350 cm (approx.)

30x 11 x 11 ft (approx.)

Coachella Music Festival

Indio, California, 2017

Featured on:

1. Rolling Stone

2. Vogue

3. Architects News Paper

4. Artnet

5. Flaunt

6. LA Times

7. La Magazine

8. Design Boom

9. Grazia

10. Arch Daily

11. Art Infused

12. Popload

13. FFW

14. Nylon Magazine

15. Ilustrada - Folha de São Paulo

16. Uol

Interview with Francesca Fiorentini for

Coachella's Youtube channel.

Entrevista com Mila Burns para Globo Internacional.

Excerpt from Coachella's website:

For the Brazilian artist Gustavo Prado, migration doesn’t end with the move. Then there’s the ongoing effort of determining “how much of your original self you’d want to maintain” and how much to “leave behind,” says Prado, who emigrated to the United States six years ago. For his “lighthouse” (the uppermost curve pointing south toward another country), Prado arranged thousands of rounded mirrors at “concurrent yet separated angles” to create a tower from light-catching fragments. “It’s a way to empirically present how the mind turns the continuous interconnectedness of phenomena into separate beings,” Prado says of his waypost for travelers, which takes its title from the last line of the Emma Lazarus poem inscribed at the the Statue of Liberty.

Few things seem more isolating than a selfie – or, better yet, a mirror selfie – but self-reflection broadens into inclusion for Prado, who studied industrial design and philosophy before turning his attention to art. Viewers lured in by the sculpture’s polished finish will find their faces among others’, shattering the “illusion of fixed identity,” he says. “You are driven to approach the piece for a very selfish and individualistic reason – to see what it does to your own reflection, and what you get is this collection of parts of multiple bodies,” Prado says. “The changes produced by the mirrors are not limited to a well-defined geometric, enclosed space and a body that walks in it. It encompasses the changes in light during the day, a much larger landscape, and all of its idiosyncratic qualities. But, more importantly, a group of viewers” – the not-so-huddled masses – “that now overlap each other as they approach”

Measure of Dispersion (2014-ongoing) is a series of sculptural installations that aim to amplify and manipulate the spectator’s field of vision. Made from concave and convex mirrors of many sizes that Prado attaches to industrial metal structures, the sculptures create something akin to an anti-camera that reconfigures the viewer’s vantage point and amplifies notions of (dis)location.

Rather than capturing a specific moment like a camera, the mirrors reflect a fragmented body seen from uncontrollable angles and different points in space simultaneously. The resulting viewer experience is a challenge to the impulse to project preconceived assumptions onto what we see: we are made to test our sense of familiarity with our surroundings and, more importantly, with ourselves.

For the Brazilian artist Gustavo Prado, migration doesn’t end with the move. Then there’s the ongoing effort of determining “how much of your original self you’d want to maintain” and how much to “leave behind,” says Prado, who emigrated to the United States six years ago. For his “lighthouse” (the uppermost curve pointing south toward another country), Prado arranged thousands of rounded mirrors at “concurrent yet separated angles” to create a tower from light-catching fragments. “It’s a way to empirically present how the mind turns the continuous interconnectedness of phenomena into separate beings,” Prado says of his waypost for travelers, which takes its title from the last line of the Emma Lazarus poem inscribed at the the Statue of Liberty.

Few things seem more isolating than a selfie – or, better yet, a mirror selfie – but self-reflection broadens into inclusion for Prado, who studied industrial design and philosophy before turning his attention to art. Viewers lured in by the sculpture’s polished finish will find their faces among others’, shattering the “illusion of fixed identity,” he says. “You are driven to approach the piece for a very selfish and individualistic reason – to see what it does to your own reflection, and what you get is this collection of parts of multiple bodies,” Prado says. “The changes produced by the mirrors are not limited to a well-defined geometric, enclosed space and a body that walks in it. It encompasses the changes in light during the day, a much larger landscape, and all of its idiosyncratic qualities. But, more importantly, a group of viewers” – the not-so-huddled masses – “that now overlap each other as they approach”

Measure of Dispersion (2014-ongoing) is a series of sculptural installations that aim to amplify and manipulate the spectator’s field of vision. Made from concave and convex mirrors of many sizes that Prado attaches to industrial metal structures, the sculptures create something akin to an anti-camera that reconfigures the viewer’s vantage point and amplifies notions of (dis)location.

Rather than capturing a specific moment like a camera, the mirrors reflect a fragmented body seen from uncontrollable angles and different points in space simultaneously. The resulting viewer experience is a challenge to the impulse to project preconceived assumptions onto what we see: we are made to test our sense of familiarity with our surroundings and, more importantly, with ourselves.